Category: good stuff from other authors

Mothers of Dragons, Brothers of Dragons. What to read in the Game of Thrones’ books hiatus?

I’m very much looking forward to the return of A Game of Thrones on the telly. Though it will be a different experience this year. I won’t have to spend the next couple of months trying to telepathically divine if an article I’m about to read will include a massive potential spoiler from someone who’s already read the books. Because while I’m up to date now, I hadn’t read any of the stories behind the series before it hit the screens.

Wait, what, how? I’m an epic fantasy writer, surely… But here’s the thing. I find it incredibly hard to read epic fantasy for enjoyment while I’m actively writing a novel in that genre myself. I’m too focused on issues of craft and analysis to just lose myself in a story. I did buy a copy of A Game of Thrones back in 1999 but it sat on the TBR shelf for years…

Until word of the television series spread. At which point I very firmly put it aside. Because I wasn’t about to miss the opportunity of seeing an epic fantasy on the screen where I didn’t already know the plot. One of the things that’s stayed with me ever since watching The Fellowship of the Ring with my then-young sons, was how very different their viewing experience was to mine, since they had no idea what was coming next. As far as they were concerned, Gandalf was dead and done with. In The Two Towers, they were on the edges of their seats with anxiety over the outcome of Helm’s Deep. Actually, one of them ended up on my lap. I wanted something of that for myself for a change. By and large, I’ve mostly succeeded.

Then, at the end of each season, I’ve read the books up to the point the TV story has reached. That’s been extremely rewarding, as a reader and as a writer. I’ve had the visuals and voices from the production’s designers and actors to enhance my imagination. I’ve also had the chance to appreciate the adaptation’s choices and to assess the different opportunities and impacts on offer through written versus visual storytelling.

What now, though? I won’t have The Winds of Winter to hand when the end credits on Series Six’s final episode roll. Happily there’s plenty of other epic fantasy to read, so how about we share a few recommendations? Need not necessarily contain dragons. I’ll kick things off by recommending Stella Gemmell’s The City – with the review I wrote for Albedo One magazine below.

Though you needn’t write a lengthy analysis in comments yourself – the title and author is sufficient. That said, feel free to share what makes you particularly enthusiastic about a book and/or to flag up a review elsewhere.

Stella Gemmell – The City (Bantam Press/Transworld)

The reader’s double-take here will be because while Gemmell is a name synonymous with the gritty, realistic tradition, this story is written by Stella, not David. Surely this makes the debut novel hurdle ten times higher than it is for most writers. How many people will read such a book primed to dismiss it as shameless cash-in or pale imitation? Even though it’s a matter of record that Stella Gemmell is a journalist in her own right and worked with her husband on his Troy trilogy, concluding the last one after his death. Well, I didn’t read the Troy series; as a Classics graduate I very rarely read anything derived from texts I studied so thoroughly at university. So I’m coming to The City entirely new to her writing.

Stella Gemmell’s skills as an author are immediately apparent. There’s a sophistication in the story-telling as the episodic structure commands attention and engagement from the readers. A disparate and separated cast of characters are initially wandering the sewers beneath a great city, reminiscent of Byzantium but with a character all its own, and troubled by the first hints of slow-moving disaster. Though the flood that sweeps through the sewers is anything but slow-moving, sundering and reassembling the men, women and children who we’ve just met. Bartellus, former general, disgraced and tortured for a crime he’s not even aware he committed and no one ever explained. Elija and Emly, fugitive and orphaned children who barely remember daylight. Indaro, warrior woman, torn between her duty and her longing to escape what she’s seen and done.

When the flood has come and gone, the story has leaped forward and the reader must work out how this fresh narrative relates to what has gone before, and fathom links between old and new characters such as Fell Aron Lee, aristocrat and famed general coming up hard against the unwelcome realities of life as an epic hero. Meantime, readers must also piece together the emerging pieces of the plot, by which I mean both the story itself and the conspiracy that’s developing to challenge the Immortal Emperors. It’s their insistence on perpetual warfare which is ruining so many generations’ lives. Gradual revelation poses successive questions which prove to have unexpected answers. From start to finish, the tale is impressively paced with constant surprises, not least where apparently trivial elements seeded early on come to fruition, and as the scope of the storytelling goes beyond the City itself, to show us its place in the wider landscape and the history of this world.

There’s more than enough death and brutality to satisfy grimdark fantasy fans but from the outset there’s something more and richer. There’s compassion in Stella Gemmell’s writing that’s all too often lacking in current epic fantasy, leaving those stories sterile and readers distanced. Here, readers will be drawn into caring over the fate of even minor characters. More than that, the rising death toll isn’t merely there to thrill readers with vicarious slaughter. Just as Gemmell assesses the cost to common folk of selfish noble ambition, she also reveals how the suffering that results is essential to creating men and women with the dogged endurance, physical and mental, needed to challenge their Imperial masters. Especially since this is epic fantasy, not alternate history, and that means magic at work. Gemmell thinks through all the implications of the Immortals’ sorcery with the same mature intelligence, right to the very last page, leaving the reader to ponder what might follow after the book is closed.

This is the most satisfying, intelligent and enthralling epic fantasy I’ve read in many a year. It stands comparison with the finest writers currently developing and exploring the enthralling balance between realism and heroism in the epic fantasy tradition that David Gemmell pioneered.

Out and about, in person and online

They* tell you that writing is a solitary occupation. Only when it comes to the pen on paper, fingers on keyboard bit. They* really should say how much fun and inspiration there is to be had in this writing life when you get together with other writers and with readers.

In the Olden Days~, that meant meeting up in person, and we still have many and varied ways of doing that in SF& Fantasy circles. This Saturday past I was in Bristol at The Hatchet Inn, for the Launch Extravaganza celebrating the publication of ‘Fight Like a Girl’. (ebook also available). This is an anthology I’m really pleased to be part of, sharing my take on this particular theme alongside established voices and newer writers in SFF.

Isn’t that such a great cover? And for the curious, those are my battle axe earrings on the right hand side. They seemed like appropriate jewellery for the day.

We had a great time, with readings from Lou Morgan, Sophie E Tallis and Danie Ware, a panel discussing this anthology’s inspiration in particular, and wider issues facing women in genre publishing, and then Fran Terminiello and Lizzie Rose (of The School of the Sword) demonstrated some fascinating swordplay, by way of a speedy run though the evolution of swords from the Medieval to the Renaissance. Great stuff.

And yes, as promised in my previous post, I demonstrated some aspects of aikido to prove that fighting like a girl may well be different to battling like a bloke – but it’s no less effective 🙂 With thanks to Fran for allowing me to demonstrate that bringing bare hands to a knife fight is not necessarily a problem, as well as the chap whose name I didn’t catch, who had done some aikido and generously allowed me to put him on his knees a few times and to show how being shorter is no disadvantage when it comes to getting a 6’3″ man off his feet. At which point gravity does pretty much the rest of the work…

(There may be photos/video in due course. If so, I’ll add links)

But that’s not all! These days we can meet up and swap thoughts, ideas and recollections online and a whole bunch of us writers are currently doing that over on Marie Brennan‘s blog. She’s celebrating the tenth anniversary of her first publication with a series of posts Five Days of Fiction, sharing her own thoughts on a series of questions and inviting others to chip in. I always find seeing what other people say in this sort of thing absolutely fascinating.

*’They’ being people whose knowledge of the writing life extends as far as repeating cliches and no further.

~ Twenty years ago.

Guest post – Zen Cho on ‘My Year of Saying No’.

You’ll recall how much I enjoyed reading Zen Cho’s debut novel, Sorcerer to the Crown. (If you missed my review, click here) So I’m extremely pleased to host this illuminating and thoughtful post reflecting on that story’s origins and her experiences as a newly published writer.

My year of saying no

In 2015 I became super obsessed with the BBC miniseries Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell. This wasn’t terribly surprising – I love the book and have reread it several times, and the series had everything I like: men and women in pretty period outfits, magic, humour, and even a touch of the numinous. It wasn’t a perfect adaptation, but an adaptation that’s sort of almost there but not quite is perfect for inducing fannish obsessiveness.

What was new and surprising was that, for the first time, I started identifying with Jonathan Strange. Jonathan Strange is nothing like me. He’s a fictional rich white dude who would be dead now if he was ever alive. I’m a real middle-class Chinese Malaysian woman who’s only spent time in 1800s England in her imagination. He’s the Second Greatest Magician of the Age. I’m a lawyer who moonlights as a moderately obscure fantasy writer.

I’m also fundamentally not as much of a douche (I love the character, but it’s gotta be said). I take no credit for this. It is because I was socialised as a woman and was therefore taught things like listening skills and how to feel guilty for taking up space in the world.

But there was one big thing I had in common with Jonathan Strange. We had both figured out what we’d been put on earth to do, and we were doing it. The vocations we had each chosen were potentially of great value and importance to society as a whole — magic in Jonathan Strange’s case; writing in mine — but we were mainly doing it for selfish reasons rather than to benefit anyone else. Nevertheless our work felt like a great and serious charge, and what this charge required of us was a determined selfishness.

In 2015 my first novel came out. It was a bit like getting married: it meant that something that had been private suddenly became very public, and people treated me differently about something I’d been working away quietly at for years. And it also meant that people started wanting stuff from me. They wanted me to answer questions, write blog posts, submit to anthologies, show up to events, blurb books, critique manuscripts ….

In 2015 my first novel came out. It was a bit like getting married: it meant that something that had been private suddenly became very public, and people treated me differently about something I’d been working away quietly at for years. And it also meant that people started wanting stuff from me. They wanted me to answer questions, write blog posts, submit to anthologies, show up to events, blurb books, critique manuscripts ….

It’s nice to be wanted, of course, and it was a refreshing novelty. As with most writers, rejection is the backing track of my life, so it was nice for once to hear “please will you?” instead of “no, thank you”. But it meant I had more demands on my time than ever before, when I had less time than ever before.

I had to learn to say no. Which was hard, because women aren’t encouraged to say no, and they especially aren’t encouraged to refuse to help other people. We’re supposed to be nurturing. Fortunately, I am pretty bad at being nurturing, but even so I struggled.

A lot of the requests I get are for nice things, things that support diversity in SFF and publishing, which is something I both care about and benefit from. How could I refuse when it was for such a good cause?

But I realised that if I was not ferociously protective of my time — if I didn’t play that role of The Rude Genius — I would soon find it sucked up in mostly uncompensated labour, in things that weren’t writing my own stories.

I don’t, in fact, have a room of my own. I have a sofa and an inbox full of requests for publishing advice that the querier could Google for themselves. So I’m learning to patrol the boundaries of the uncluttered space I need for writing — and for living, because I don’t owe anyone time and attention even if I’m not rushing to meet a deadline.

I’m still not as good at saying no as I should be, but I’ve already been accused of being grand for the appalling crime of not answering emails. I wonder whether the same accusation would be lobbed at me if I was a white man. We expect men, especially white men, to be rude geniuses. But it seems we feel entitled to the time and energy of women, especially Asian women.

You’ll point out I’m not a genius, which is true, but then I’m also not that rude. I say yes far more often than I say no. There’s still that fear, whenever I turn something down, that I should make the most of any attention I’m getting now, because people will stop asking eventually.

But you know what? I have never, not once, regretted saying no. And even if people stop asking and go away, it’s not like they’ll take the stories with them. Writing is mine – and it would be foolish to let a general sense of obligation to the world at large chip away at it. Jonathan Strange would definitely say something sardonic about that.

Sorcerer to the Crown by Zen Cho – a review

In Regency London, the Royal Society for Unnatural Philosophy has its first African Sorcerer Royal, Zacharias Wythe. Unsurprisingly, this does not please the great and the good (self-proclaimed) of English Magic. Zacharias, erstwhile child slave and later ward of the former Sorcerer Royal, Sir Stephen Wythe, is well aware of their enmity but has far more urgent concerns. English magic is being steadily depleted and relations with Faerie, a vital source of power, have somehow been dangerously compromised. Add to that the British Government is pressing Zacharias to endorse and support their imperial ambitions in Indonesia. This raises the very real danger of French sorcières deciding such actions breach the longstanding gentleman’s agreement against magical involvement in the Napoleonic Wars.

In Regency London, the Royal Society for Unnatural Philosophy has its first African Sorcerer Royal, Zacharias Wythe. Unsurprisingly, this does not please the great and the good (self-proclaimed) of English Magic. Zacharias, erstwhile child slave and later ward of the former Sorcerer Royal, Sir Stephen Wythe, is well aware of their enmity but has far more urgent concerns. English magic is being steadily depleted and relations with Faerie, a vital source of power, have somehow been dangerously compromised. Add to that the British Government is pressing Zacharias to endorse and support their imperial ambitions in Indonesia. This raises the very real danger of French sorcières deciding such actions breach the longstanding gentleman’s agreement against magical involvement in the Napoleonic Wars.

So the last thing Zacharias needs is the eruption into his life of Prunella Gentleman, half-Indian orphan and pupil-teacher at Mrs Daubeny’s boarding school, where well-born girls unfortunately afflicted with magical talent are trained to restrain such unseemly impulses. After all, everyone knows that women are unsuited to thaumaturgy. Well, everyone except Prunella. And the witches of the Banda Strait. What with one thing and another, Zacharias can’t even find refuge in the congenial surroundings of his club, The Theurgists.

This is an entertaining and original addition to the Regency fantasies we’ve seen expanding and enriching the genre in recent years. Not least because Cho is drawing on up-to-date historical sources, including non-Eurocentric views of that era, as well as the literature of the period rather than anyone else’s later and potentially anachronistic interpretations. She evidently knows her Austen, and her Thackeray and more besides, I shouldn’t wonder. The attitudes of the English aristocracy, both in terms of class and race, are entirely of their time, as indeed are Zacharias’ and Prunella’s reactions to the prejudices and insults they face, whether incidental or intentional. Their friends and foes are similarly, satisfactorily rounded and believable.

Crucially, none of this exploration of attitudes to sex and/or race is mere set-dressing or clumsy polemic. It all drives the fast-paced plot by informing decisions and plans on both sides of the growing conflict. Action prompts reaction and dangers escalate. Now Zacharias’s outsider status gives him a different perspective on non-English and non-European magical traditions. Meanwhile Prunella’s determined to put her own magical resources to best use, to learn what she can of her parentage and to make a satisfactory marriage. However her naivety means she has scant idea of the consequences of her actions. Some of these outcomes are comical; Cho has a deft touch with humour. Others are chilling. Cho doesn’t compromise over the grimmest implications of the opposition to Zacharias, or the measures that must be taken to defeat it.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. It’s absorbing and well written fantasy enriched with a meaningful hinterland. So I am not surprised to see enthusiastic cover quotes from writers as diverse as Naomi Novik, Ann Leckie, Charles Stross, Lavie Tidhar and Aliette de Bodard. I’m very much looking forward to the sequel.

To find out more about Zen Cho and her books, click here for her website.

Discussing diversity & representation in SFF – links round up

My post on the erasure of women last Monday clearly struck a resounding chord, which I find extremely encouraging. Though I’m by no means the only, or indeed the most recent, writer to post reflections on this issue. Here’s a selection of pieces I’ve found well worth reading recently.

I’ve pulled some quotes to give you a flavour of the pieces – and I urge you read them in full. Then go and read these authors’ books. I personally enjoy all their work – the books are well written, engaging, intriguing, entertaining. Better yet, the way these authors really think through what they’re writing, about who, how and why, gives their stories satisfying richness and depth,.

Here’s an excellent piece by Judith Tarr over on Charlie Stross’s blog. “What goes around…”

It can get really, really tiresome to fight the same battles over and over and over again, and to watch the older battles and the women who fought them be systematically and consistently erased. But when I realize how deeply ingrained the silencing of women is, I find it all the more remarkable that there’s actual, perceptible progress. Women’s voices are actually being heard–and sometimes even being taken seriously.

“is my malfunction so surprising ’cause I always seem so stable and bright?” asks Elizabeth Bear.

See, the funny thing is, it turns out that people of color and queer people and women and genderqueer people and disabled people… we’re not types. We’re not categories. We’re individuals with certain characteristics and we may have very different attitudes and philosophies and relationships with those characteristics.

So, saturation matters. We need a lot of stories with different kinds of people in them, and not just a token stereotype, one per book or movie or TV show.

And actually, finally seeing yourself as a protagonist or a significant character in art is a tremendously empowering experience. Seeing yourself reflected makes you feel real and noticed, and it’s important.

Since it’s vital that this debate includes a fully representative range of voices, I am indebted to Stephanie Saulter whose Twitter feed alerted me to this next piece from Tor.com.

“Writing Global Sci-Fi: White Bread, Brown Toast” by Indrapramit Das

Growing up with these imaginative riches curiously absent from Indian contemporary art and media, I didn’t even notice all the white protagonists, writers, directors, and actors in this boundary-less creative multiverse I so admired and wanted to be a part of. Or I didn’t mind this prevailing whiteness, because I was taught not to. That, of course, is the quiet hold of cultural white supremacy.

It wasn’t until I was on a campus in the middle of Pennsylvanian Amish country, surrounded by young white undergrad creative writing students in a workshop class taught by a white professor, that I realized I mostly wrote white protagonists. I’d never felt less white, which made the repeated pallor of my protagonists blaze like a thousand suns.

…

I’m not apologizing for growing up inspired by so much science fiction made by white people primarily for white people. Hell, I think white creators should be proud that their work found fans across the planet, and acquired some shade of the universality that sci-fi is supposed to espouse in its futurist openness. Just as languages spread and mutate on the vector of history (I see no need for gratitude, explanations, or shame for the words I use just because they were introduced to India by colonizers—Indian English is no different than American English or Quebecois French), so too do genres and art, and it’s time to recognize that sci-fi and fantasy are so dominant in pop culture now because fans the world over helped make it so. But if international sci-fi is to change, instead of stagnate into a homogenous product for the algorithm-derived generic consumer, it needs to foreground the profuse collective imagination of the entire world, instead of using it as background color for largely white stories.

I’m also including this piece by Jim Hines – My Mental Illness is Not Your Inspirational Post-it Note for two reasons.

Firstly, diversity is about showing and allowing access to every marginalised group – and all at the same time. It’s long past time to do away with the ‘Highlander’ approach to representation, insisting “There can be only one!” so if people of colour (or any other group) want the single ‘Minority Seat’ at the table, white women (or whoever else might be sitting there at the moment, but oddly, never the white men in the rest of the chairs) must take a step back.

Secondly, the piece underlines the importance of getting things right and actually listening, if you want to be an ally, and even more so if you’re writing about a group you’re not personally a part of.

This is a group that’s set themselves up as advocates for people with mental illness…while ignoring feedback from the very group they claim to support. I don’t know the individuals behind Team Notashamed or their situation, but this feels like symptoms of Toxic Ally Syndrome, where you’re so determined to be an “ally” of Group X that you ignore or argue with members of Group X because you know best. This is often followed by choruses of, “Why are you getting angry at me? I’m your ally! Fine, if you’re gonna be so ungrateful, I’ll just take my allyship and leave!”

Right, that’s enough to be going on with. That said, feel free to flag up any other good pieces you’ve come across in comments.

EDITED TO ADD –

The Geek’s Guide to Disability by Annalee over at The Bias blog.

I want the science fiction community to be inclusive and accessible to disabled people. I want our conventions and corners of the internet to be places where disabled people are treated with dignity and respect. I’m hoping that if I walk through some of the more common misconceptions, I can move the needle a little–or at least save myself some time in the future, because I’ll be able to give people a link instead of explaining all this again.

for instance

The use of “differently abled” is especially a problem within the science fiction community because it feeds the myth the people with disabilities develop compensatory superpowers. Some of us read and watch so much bullshit about disability that we have to be reminded that Daredevil is a comic book and not a documentary.

I’m using DareDevil as my example ‘supercrip’ because a lot of folks honestly believe that blind and low-vision people develop heightened senses of hearing and touch. The evidence for that is, at best, inconclusive. (The National Federation of the Blind says flat-out that blind people don’t develop sharper senses).

Once again, I strongly recommend reading the whole piece.

Guest post – Simon Morden discusses Down Station and portal fantasy.

A new book that I very much enjoyed reading this month is Simon Morden’s Down Station. For a fuller assessment, you can read my review in the next issue of Interzone.

A new book that I very much enjoyed reading this month is Simon Morden’s Down Station. For a fuller assessment, you can read my review in the next issue of Interzone.

For those of you unfamiliar with Simon’s work, his website is here – and for a chance to meet him, along with Tricia Sullivan, author of Occupy Me, they’re both signing at Forbidden Planet, Shaftsbury Avenue, London on 20th February, 1-2pm. Simon will also be a guest at the Super Relaxed Fantasy Club on 23rd February.

One of the things that particularly interests me about Down Station is the fact that it’s a portal fantasy. So I invited Simon to share some thoughts on that particular topic.

In defence of Narnia and other portals Simon Morden

I recently discovered that Narnia* is a real place. Quite how that fact has eluded me for my entire adult life is a complete mystery, but I have a sudden hankering to go there and make an in-depth investigation of their wardrobes.

Because you would, wouldn’t you? Or did you grow out of that urge? The ghost of the Susan argument rears its ugly head: wanting to escape this world, with its social and economic obligations and constraints, is something that a child would do, kicking against the goads of adulthood. When a person knows their place in society and accepts it, they no longer need such escapist diversions.

Lewis, however, was speaking of a more fundamental truth even as he got it hamfistedly intertwined with 1950s social mores. Rather than agreeing that wanting to escape to another place is a mere childish notion, to be discarded as we embrace a more mature understanding of our own world, he was proposing that it’s us – the grown ups – who are the ones who lose out.

The belief that our world lies side by side with others wasn’t invented by Lewis. It goes far back, beyond recorded history. In my native islands, the Celts believed the Otherworld was connected to us at certain times of year and in certain sacred places. People could cross over, usually by invitation rather than trickery, and sometimes even return. With the coming of Christianity, these became the ‘thin places’, where Heaven and Earth pressed together, but the result was always the same: those who came back were forever changed, either by their experience of the Other, or of the Divine.

Throughout history – and prehistory – the point of these stories was that the intrepid travellers to other worlds were never escaping: they were questing. They went for a reason – either to gain something which could be used in our world, be it wisdom, a skill, or an artefact, or to give something to that other world, to save it from evil or break a curse. That we’ve turned – some might say corrupted – an important facet of our mythology into a genre that adults shouldn’t consciously entertain is problematic, to say the least.

At its worst, yes, Sturgeon’s Law (that 90% of everything is crap) applies. A portal fantasy can be all those things their critics say it is: cliche-ridden wish-fulfilment in which nothing is at stake. Perhaps, after a while, these overwhelm the market and the whole genre goes out of fashion. Certainly, anecdotally, portal fantasies have been a tough sell for years. There were always exceptions: May’s Pliocene Saga and Pullman’s His Dark Materials being perhaps the most notable. But here we are, like buses, with two coming along at once, my Down Station and Seanan Mcguire’s Every Heart a Doorway. We’re probably at the cutting edge of a new wave, and editors across the land will hate us in six months’ time for unleashing a torrent of portals across their desks. For now, though, they represent something different to the usual fare.

I would like to think I’ve done something new with my own portal(s). Featuring non-standard protagonists is a start, being chased across the threshold is another, and the world of Down itself owes more to Tarkovsky’s Solaris than it does Narnia. But I’ve done something old, too, as old as time itself. Down is a place of challenge – there are secrets to be uncovered, battles to win, knowledge to be retrieved, and two worlds to save – and change, both mental and physical. The three questions that recur in Babylon 5 – Who are you? What do you want? Do you have anything worth living for? – are circumvented by Down, because it already knows the answers, even if you’re in denial.

At its best, portal fantasy offers us a narrative metaphor for seismic shifts in our cognitive landscape. Because our image is clearly reflected in the mirror, it can help us better decide if we like what we see. If we cross over to the Otherworld, we come back different people, if we come back at all. The portal is not a way out, but the way in.

Guest Post – Jacey Bedford on whether she writes SF or F?

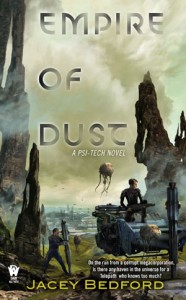

As I’ve mentioned previously, I’m very much enjoying Jacey Bedford’s Psi-Tech novels, namely Empire of Dust and Crossways, which are thoroughly good space-opera ticking all the boxes that first made me love SF while also thoroughly satisfying to me as a contemporary reader. So I was both startled and intrigued to learn that her new book, Winterwood, is a historical fantasy, set around 1800, with pirates and spies and mysterious otherworldly creatures all entangling Rossalinde Sumner in their machinations. You won’t be surprised to learn I invited Jacey to tell us all about that, and she has generously obliged.

SF or F? Trying to work out the differences and similarities.

With Winterwood, the first book of the Rowankind Series, on the brink of publication, Juliet asked me to write about transitioning between writing science fiction and fantasy. I sat down to think about it, but the more I worked on the differences between the two, the more similarities I came up with.

For starters, from the outside it does look as if I made a switch in genres, but it’s not quite the way it looks from the inside. My first two books to be published. Empire of Dust (2014) and Crossways (2015), are science fiction/space opera, but it’s a quirk of the publishing industry that they came out first. Winterwood, my historical fantasy, was actually the first book I sold to DAW, back in 2013, but it was part of a three book deal. DAW’s publishing schedule was such that there was a gap in the science fiction schedule before the fantasy one, so Empire of Dust ended up being published first. The order of writing, however, was Empire, Winterwood, and Crossways.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Let me backtrack. The road to publication is often slow and tortuous. Many of us who eventually make it have a drawer full of completed books before getting the magic offer from a publisher. These aren’t necessarily bad books or rejected ones, but ones that have not been on the right editor’s desk at the right time. The difference between a published writer and an unpublished one is often, simply, that the unpublished one gave up too soon. I started writing my first novel in the 1990s without any hope of finding a publisher, and with no knowledge of how to go about it, even if I’d been brave enough to try. That, however, was all about to change – mostly because of the internet. Once I got online in the mid 90s I connected with real writers via a usenet newsgroup called misc.writing, and learned all the basics about manuscript format and submission processes. (And yes, I’m still in touch with some of those very generous writers two decades later.) While all this was going on I finished a couple of novels and made my first short story sale.

The two early novels, at first glance, were second world fantasies, but the deeper I got into them the more I realised that they were actually set on a lost colony world. There are places where science fiction and fantasy cross over to such a degree that it’s hard to see where the boundary is. My lost colony world had telepathy but no magic. So thinking about it logically, how did that colony come to be lost? What put telepathic humans on to a planet and then kept them there, isolated from, and ignorant of, their origins?

That was the question that I started writing Empire of Dust to answer (though it may take all three Psi-Tech books to do it). Because the story involved planets, colonies and space-travel, I was suddenly writing science fiction. I don’t write hard, ideas-based SF. I’ve always been far more interested in how my characters’ minds work than what drives their rocketships, though I’ll always try to make the science sound plausible if I can.

Characterisation – that’s always the crux of the matter for me. Take interesting characters and put them into difficult situations and see what they do. It doesn’t actually matter whether they are in the past or the future, or even on a secondary world, what matters is that the characters grow and develop via the story to overcome problems and reach a satisfactory conclusion. Well, OK, the setting matters, but it’s not always the first thing that hits me. The setting and the detailed worldbuilding grows around the characters and weaves through the story, adding context and interest, and sometimes becoming a character in its own right.

So Empire of Dust, in a much earlier form, was finished in the late 90s and then began the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. Remember what I said about persistence? Well, I’m dogged, but not always very pushy. Empire sat on one editor’s desk at a major publishing house for three years after the editor in question had said: ‘The first couple of chapters look interesting. I’ll read it after Worldcon.’ It took me three years to figure out I should withdraw it and send it somewhere else. Then the next publishing house it went to took another fifteen months. Those kind of timescales can eat up a decade very quickly. (I know one author who took to sending her languishing submissions a birthday cake after a year.)

In the meantime I kept on writing. It just so happened that the next three books were fantasies unrelated to each other: a retelling of the Tam Lin story aimed at a YA audience; a fairly racy fantasy set in a world not dissimilar to the Baltic countries in the mid 1600s, and a children’s novel about magic and ponies (not magic ponies). Why fantasy? I think I instinctively wanted to widen the scope of what I was doing to take in a wide variety of settings, however it was still mainly dictated by the characters.

If story and character are a universal constant, surely the difference between writing science fiction and fantasy is all down to worldbuilding. Right? Uh, well, maybe…. Science fiction can (to a certain extent) be fuelled by handwavium based on the accumulated reader-knowledge of how SF works. SF readers have an idea of how physics can be bent without being completely broken, whether you’re talking about the physics of Star Trek (warp-drives, photon torpedoes), or the hard SF of Andy Weir’s The Martian (which I love, by the way). When you write fantasy, you don’t have Einstein to fall back on. You have to work out how your fantasy world works from the ground up. If there’s magic, the magic system has to be logical and not contradictory (unless you build in a reason for the contradictions). If it’s set on a secondary world you might have strange creatures, races other than human, or even gods who act upon the world or the characters. Though, come to think of it, aliens, strange flora and fauna, and even ineffable beings are obviously common to science fiction as well. And when I said fantasy doesn’t have Einstein to fall back on, it does have the accumulated folklore of several millennia to point the way.

I think I’ve just talked myself round in a circle. So far, so similar.

So I started my next project, Winterwood, around 2008. By this time Empire of Dust had had three near misses with major publishers, but was still doing the rounds.

Winterwood almost wrote itself. I had the first scene very firmly in my mind – the deathbed scene – a bitter confrontation between Ross and her estranged mother. I wrote it to find out more about the characters and their situation. Ross hasn’t seen her mother for close to seven years since she eloped with Will Tremayne, but now her mother is dying. About halfway through the scene Ross’ mother asks (about Will): ‘Is he with you?’ Ross replies: ‘He’s always with me,’ and then follows it up with a thought in her internal narrative: That wasn’t a lie. Will showed up at the most unlikely times, sometimes as nothing more than a whisper on the wind. That was an Ah-ha! moment. I realised that Will was a ghost. Ross was already a young widow. That led me deeper into the story and gave me another character, Will’s ghost – a jealous spirit, not quite his former self, but Ross is clinging to him because he’s all she has left. That sets the scene nicely for when another man finally enters Ross’ life, but the romance is only part of the story. Ross inherits a half-brother she didn’t know about, and task she doesn’t want – an enormous task with huge consequences. There are a lot of choices to be made, and no easy way to tell which are the right ones. Ross has friends and enemies, some magical and some human, but sometimes it’s difficult to tell them apart. Even her friends might get her killed.

When that first scene came into my head, it could have been set in any place, any time. Parents and their children have been disagreeing and falling out for as long as there have been parents and children and, I’m sure, until we decide to bring up all our offspring in anonymous nurseries, it will continue well into the future. Ross took shape as I wrote, and I realised it was set in the past, or a version of it. In her first incarnation Ross was a pirate rather than a privateer, but I wasn’t sure what historical period to set the book in. The golden age of piracy was really in the 1600s, but I wanted to set this slightly later, so I decided that 1800 was a good time to play with. It’s a fascinating period in history with the Napoleonic Wars about to kick off in earnest, Mad King George on the British throne, the industrial revolution, the question of slavery and abolition, and the Age of Enlightenment. Of course I added a few twists, like magic, the rowankind and a big bad villain, who is actually the hero of his own story, though that doesn’t make him any less dangerous to Ross.

Historical fantasy is yet another subset of F & SF. If you’re writing in a specific historical period, you can make changes to incorporate your fantasy elements, adding magic for instance, or tweak one historical, point, but then you have to make sure that there’s enough solid historical background to make the rest of it feel authentic. You’re not necessarily looking for truth, but you are hoping for verisimilitude. I’m an amateur historian, not an academic one, but I did a lot of research: reading, museums, studying old maps and contemporary photos. I have several pinterest boards devoted to visual research, costume (male and female), ships, transport and everyday objects. Whenever I find something interesting I pin it for later consideration.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

Getting a book from writer to store shelf is a multi layered process. There’s the writing and then the edit – which usually means some rewriting with additions. The once the final story has been accepted as finished it goes through copy-editing where clunky prose and spelling mistakes are smoothed over, and in my case, my British English is translated into American. Once the copy edits have been done then next part that I’m involved in is the page proofing, the final check after the book has been put into its finished form. This is the last chance to catch typos and brainos, but there’s no real opportunity to make big changes.

During the various editing processes there are gaps while your editor reads and considers, or the copy editor does his or her thing, so you tend to be working on other stuff while you’re waiting. The beginning of one book overlaps the editing process on the previous one and will in turn be at the editing and copy-editing stage when you’re just beginning to write the book after that. So, you see, it’s not like you have the luxury of working on one book at a time. The whole process is plaited together, fantasy and science fiction running alongside each other.

Winterwood comes out on Tuesday 2nd February. I’m currently writing Silverwolf, its sequel, which is due out late 2016 or early 2017. After that I’m contracted to write a third Psi-Tech novel (the aforementioned Nimbus), so it’s back to another space opera to follow on from Empire of Dust and Crossways. After that I’d like to write a third Rowankind novel. I already have ideas and there will be a few loose ends at the conclusion of Silverwolf, though, don’t worry, I never leave books on cliffhangers.

So the transition between science fiction and fantasy is not neatly delineated. It’s all mushed up together in both my writing timeline and in my brain. On the whole I just write stories set in different worlds. Some of them happen to have rocket ships, and others have magic, but all of them have characters who have adventures, relationships, and make choices, good and bad. I’m happy hopping between the future and the past, and I’m super-happy that my publisher has given me the opportunity to be an author who writes both SF and F.

You can keep current with all Jacey’s news over at her website.

P.S I’ve just finished reading Winterwood and can recommend it as highly as the Psi-Tech Novels.

Fight Like A Girl – the anthology and the launch event!

I honestly cannot recall what started that particular Twitter conversation. I’m guessing it was probably something about ‘fight like a girl’ being used as some throwaway insult, prompting derision from the very many of us women with hands-on experience of a broad range of martial arts and skills. Somehow – rather splendidly – the discussion morphed into ‘how about an anthology…?’

The rest is history. The future is this splendid book from Grimbold Books, who ask –

“What do you get when some of the best women writers of genre fiction come together to tell tales of female strength? A powerful collection of science fiction and fantasy ranging from space operas and near-future factional conflict to medieval warfare and urban fantasy. These are not pinup girls fighting in heels; these warriors mean business. Whether keen combatants or reluctant fighters, each and every one of these characters was born and bred to Fight Like A Girl.

Featuring stories by Roz Clarke, Kelda Crich, K T Davies, Dolly Garland, K R Green, Joanne Hall, Julia Knight, Kim Lakin-Smith, Juliet E McKenna, Lou Morgan, Gaie Sebold, Sophie E Tallis, Fran Terminiello, Danie Ware, Nadine West “

Fans of The Tales of Einarinn might like to note that my story, ‘Coins, Fights and Stories Always Have Two Sides’ takes place in during the Lescari Civil Wars, before the events of the Chronicles of the Lescari Revolution.

When can you get hold of a copy? Well, we’re launching the anthology with an event in Bristol on Saturday April 2nd from 1-5.30pm, at the Hatchet Inn, 27-29 Frogmore St, Bristol, BS1 5NA in association with Kristell Ink and Bristolcon. (Isn’t the collaborative, supportive nature of SF&F great?)

It’ll be a sociable and fun afternoon including swordplay and display, discussing the role of women in SF&F (both as characters and authors), excerpts from the book, and a buffet. Whether you’re a budding writer, established author or genre fan, there will be something for everyone!

You can book tickets here – please note that the £5 is to cover the cost of the buffet (and the 95 pence is Eventbrite’s administration fee). Overall, the event is being funded by the Bristolcon Foundation.

I’m really looking forward to it. See you there, to help fly the FLAG?

Creative writing articles – the latest link & a new permanent webpage to round up the rest

I’ve had a couple of invitations recently to write guest articles on different aspects of creative writing. You can find the first of them here at the SciFi Fantasy Network where I outline how I learned vital lessons about getting feedback, thanks to NOT getting published twenty years ago.

So that’s the first thing. Head on over and read that and feel free to pop back and let me know what you think. Meantime, on to the second thing here.

Looking for inspiration for these posts, I asked folks what would interest them and got a fine range of responses. Though in some cases, I thought, ‘hang on, haven’t I already written about that topic?’

A little research soon indicated that well, yes, I might well have written such an article but those pieces are not necessarily straightforward to find, especially when I wrote them over a decade ago!

It struck me pretty forcefully that a round-up was in order. I soon discovered that I’ve had good many and varied things to say over the years, but rather than bludgeon you with an endlessly scrolling blog post, a separate list would be more wieldy.

So here’s a dedicated page on the site to make everyone’s life that bit easier.

There’s a good range of reading for you to browse and dip into at your leisure, in roughly reverse chronological order, which is to say, the most recent at the top, oldest at the bottom, and including guest pieces by me elsewhere.

Below that you’ll find links to guest posts from other writers that have appeared on this blog.

Enjoy!

Guest Post – Tricia Sullivan on World Building and the Kobyashi Maru

Tricia Sullivan has a new book out this week, Occupy Me, and I think it’s fair to say her award-winning, idea-driven SF is worlds away from my own style of epic fantasy fiction. And yet, as is the case with a good many writers whose work is nothing like mine, we have a good few things in common; the foundation for our friendship and mutual respect. One of those things is a background in tabletop and computer gaming and Tricia’s written a fascinating article examining the relationships between that style of world building and truly creative writing.

Once you’ve read it, I’ll be very surprised indeed if you’re not prompted to find out more about Tricia and her work – if you’re not already familiar with her books!

“Kobiyashi Maru

Whenever somebody says ‘worldbuilding’ I think of Gary Gygax straight away. I think of polyhedral dice, graph paper maps for dungeons, hex paper maps for outdoors. I think of the languages I tried to invent and all that other good, ooky stuff.

I was a first-generation D&D player. My brother bought it in a box in 1979. I was in fifth grade, same year I read Dragonsinger, and I remember being genuinely scared by the giant spiders and ghouls in the sample dungeon. There were hardly any modules back then, so if you gamed you really had no choice but to make it all up yourself. D&D was a great enabler of storytellers. Its codification, numeration and classification of every damn thing both encouraged worldbuilding—by providing scaffolding—and also inhibited it—because D&D turned reality into a Lego set.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m very fond of Lego, but you have to admit the results are always pretty…well…square. D&D was square like that, too. I hated how designing anything in it was the equivalent of filling out 40,000 pages of requisition forms, ticking boxes all the way.

When you are building worlds, sometimes you want Lego, but other times you want Play-doh. Sometimes you want to be able to bend it and squish it. In the pre-digital era it used to be possible to express things without having to first establish the rules and the codes. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that D&D was coming in at the same time as Apple and Atari—it was more flexible than writing code, but at heart the game was all about the rules. And taken to the limit, the rules of the world can become more important than the thing you are trying to do.

Fictional worldbuilding is like that, too. You want the story to take flight in the reader’s imagination, but you never want the reader to see the billions of robots running around behind the scenes pulling leavers and heaving things into position. You’ve got to convince the reader they are immersed. How do you do that? I reckon you have to play with what people already know about the world—but of course, most of us don’t know very much! It’s interesting to me that one of the least conventional writers I can think of, Diana Wynne Jones, nevertheless authored ‘The Rough Guide to Fantasyland’ as a plea for at least a little rigour. To work well, fantasy has to stand on the shoulders of reality.

But what does rigour even mean, these days? Culturally, we have a certain D&D-based shorthand when it comes to kingdoms, quests, character classes and expectations—all mainstreamed thanks to video games. These archetypes are pretty distorted and some of them are tired as hell, but whether the shorthand is played straight or torqued in some way, it’s pretty much embedded in the DNA of SFF across all the platforms that now deliver SFF content.

The shorthand can be a great facilitator. As a writer, it’s not hard to use a prefab world and tweak it a little for your own purposes. It doesn’t take a big deviation in initial conditions from the world as we know it to a world that seems strange and new. Once you open up the toolbox (of environment, economic systems, biological structure, culture, history, yadda yadda yadda) you have endless permutations at your disposal to experiment with ‘what if’ and to run simulations—alternative worlds to our own, if you will. This is the primary function of imaginative play. It is also very hard work.

But causal extrapolation isn’t the end game, at least not for me. In fact, it’s often a trap, a dead end, an unwinnable situation. No, the end game is imagination. The end game is magic.

Real magic—if I can indulge in the oxymoron—isn’t systemized. It’s outside our understanding, by definition. It comes out of flashes of insight, surprise, transformation. To make those kind of fireworks go off in someone’s mind is a very tricky business, and I’d argue that to make it happen as a writer, you need total control and this includes knowing when to lose control. When to let go of the wheel. A world you’ve built becomes its own organism, has its own mind, and to give it lift-off there’s a point where you throw out the rules, throw out what you think you know, and let the thing take you where it needs to go.

Gaming doesn’t teach this, and as far as I know it’s not in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, but I’ll bet artists know what I’m talking about because they build worlds, too—that’s what art is. Even as it’s using rules, art is a protest against the rules.

If you really want to fly, then just for a moment, get meta. Don’t accept the limitations you’re given. Reprogram the fucking computer that your world is running on. Beat the Kobiyashi Maru.

The dice and the graph paper will still be there when you come down.”

You can find out more about Tricia, her writing and this book in particular, over at her website