Category: Links to interesting stuff

It’s ZNB Kickstarter time! Support great stories and an open call for submissions

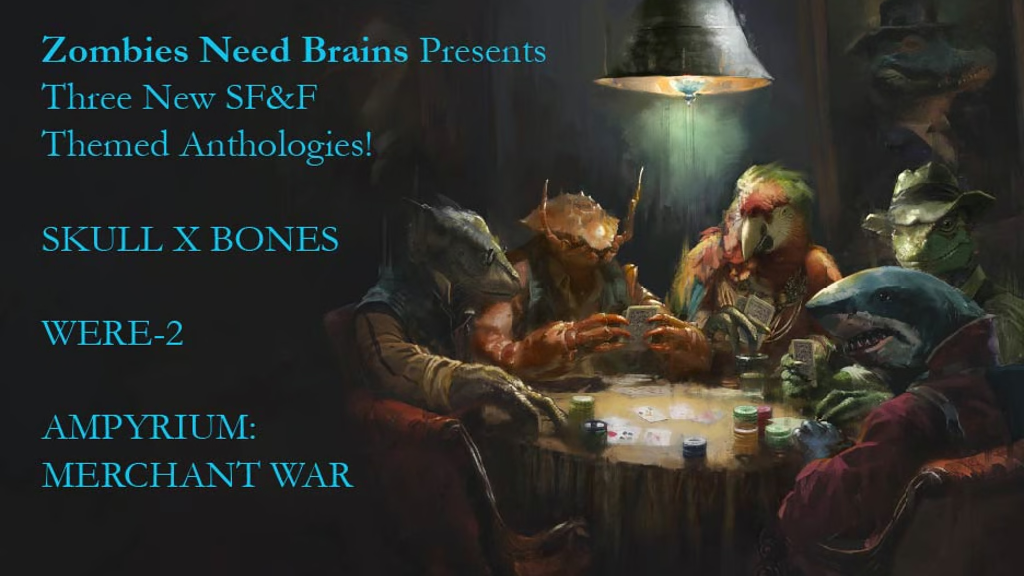

I mentioned my Ampyrium short story a while ago. I’m thrilled to say I’ll be returning to this fascinating shared world with one of this year’s ZNB anthology projects.

As regular readers will know, each year for over a decade now, this splendid US small press produces collections of original (no reprint) short stories (around 6,000 words), funded by Kickstarter. You’ll find great reading from a mix of established SF&F authors and new voices found through their open submissions call, announced once the Kickstarter is funded. Editorial standards are rigorous, and ZNB is a SFWA-qualifying market, paying professional rates.

This year’s projects are as follows:

WERE-2

It’s the night of the full moon, and in the back alleys in the dead of night, were-creatures might see you as prey. A were-raven? Were-squirrel? Were-octopus? You won’t know until you hear that rustle of feathers next to your ear or smell the brine of the sea. Editors S.C. Butler & Joshua Palmatier are looking for creative were-creature tales with only one rule: No werewolves allowed!

Anchor authors include: Randee Dawn, Auston Habershaw, Gini Koch, Gail Z. Martin & Larry N. Martin, Harry Turtledove, Tim Waggoner, and Jean Marie Ward.

SKULL X BONES

Pirates have enchanted and haunted readers for generations, from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island to the ill-fated Firefly to Black Sails and Our Flag Means Death! From swashbucklers to scruffy-looking nerfherders, David B. Coe & Joshua Palmatier want writers to come up with their best science fiction or fantasy pirates, whether they’re plundering the golden age of sail on this or some other world, or leaving the blue behind on a spaceship heading into the black.

Anchor authors include: R.S. Belcher, Alex Bledsoe, Jennifer Brozek, C.C. Finlay, Violette Malan, Misty Massey, and Alan Smale.

AMPYRIUM: MERCHANT WAR

The city of Ampyrium is bustling with trade…in the midst of a Merchant War! It is the hub for eight portals to other worlds, where goods and more change hands both above and beneath the table. Does any business escape the Eyes of the enigmatic Magnum who first created this city of magic and mayhem, saintliness and sin? What nefarious plans are now afoot?

I’ll be writing alongside my fellow anchor authors Patricia Bray, S.C. Butler, David B. Coe, Esther M. Friesner, Juliet E. McKenna, Jason Palmatier, and Joshua Palmatier – who is also our highly esteemed editor.

The Kickstarter runs until 15th September 2024 and offers bonus rewards and incentives at all levels.

The J.R.R. Tolkien Lecture on Fantasy Literature 2024 – Speaker Neil Gaiman

Living in Oxfordshire, I’m fortunately able to attend most of these lectures in person. Heading into Oxford yesterday afternoon, I already knew this would be as good as any previous year. In the twenty or so years since my path first crossed Neil’s at a convention, I’ve heard him talk many times, and he will always have something new, different and fascinating to say. This was no exception – but I’m not going to attempt to summarise, as the video will soon be available, and believe me, you really don’t want to miss that.

(While you’re waiting do check out the videos of previous years’ speakers available at the Tolkien Lecture website. Varied, fascinating and thought-provoking.)

One thing Neil said prompted me to make a note. He quoted CS Lewis quoting JRR Tolkien: ‘The only people who decry escapism are jailers ‘.

That reminded me of something which I couldn’t quite remember, if you know what I mean… I’ve found it now, and it is very well worth the read – Sherwood Smith and Rachel Manija Brown on Who Gets to Escape

That article was particularly interesting for me, given the responses I was seeing at the time to my trilogy The Hadrumal Crisis, where who can and cannot escape various situations underpins a lot of the story. I discuss that here.

One other note. As I reached the venue, Oxford Town Hall, I was struck by the tremendous variation in the ages and appearances of those waiting patiently for the doors to open. Proof, if any were needed, that there’s no readily identifiable demographic for fantasy fans. This is possibly one reason why passers-by catching buses home from work were so bemused by the queue – which was very soon reaching well down St Aldates and past Christ Church’s Tom Tower. The town hall is a big space and it was packed!

Why Do We Write Retellings? A guest post from Shona Kinsella

I’ve been back and forth with myself, pondering the answer to this question. With so many new ideas just waiting to be worked on, why do we, as writers, return to old stories? Why do some stories hold such power over us that we retell and reimagine and reexplore them over and over, centuries after they were first told? Perhaps, in some cases, it’s because there are voices in those stories which have never truly been heard, whether that’s the women of Arthurian legend as in Juliet’s The Cleaving, or Snow White from the point of view of the stepmother, as in Cast Long Shadows by Cat Hellisen. In other cases, maybe it’s following clues through history and archaeology to shine new light on old tales, as with Stephen Lawhead’s King Raven Trilogy which places Robin Hood in Wales, in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest.

Ultimately, I can’t speak for those authors, or tell you why they revisited these tales (although I can definitely recommend that you read the books, each one of them is wonderful). All I can really tell you, is why this story called to me.

So, why then did I feel the pull of a Scottish myth so old that its origins are lost to time?

Like many fantasy readers, I have always loved myth and legend and folklore, especially from Scotland. I spent a lot of time outdoors as a child, often in semi-wild places rather than in cultivated gardens and parks. I clambered over rocks on loch sides and riverbanks, made dens in the roots of trees, hunted for tadpoles and dragonflies in marshy, undeveloped land near my home, felt the wind and the sun and the rain – always the rain – on my skin as I searched for signs of the fae. Even now, though I spend more time in my office than outside, I never fail to turn my face to the sun on the first warm days of spring, to find joy in the changing of the seasons and to point out these markers to my children as we walk to school.

It is perhaps unsurprising then, that I should have such love for a myth which touches upon the lives of the gods said to govern the seasons – The Cailleach, the lady of winter, who formed the highlands by striding through the land dropping boulders from her apron; Bride, queen of spring, who is celebrated at Imbolc at the beginning of February; Aengus, god of Summer, love and poetry. It is not a particularly well-known myth outside of the Scottish highlands and certain pagan groups dedicated to the worship of one or other of these deities, which is initially how I stumbled across it. As a pagan dedicated to the worship of Brighid (also spelled Brigid, Bride, Brigit) this myth has deeply personal resonances for me.

In the original myth, The Cailleach is jealous of Bride’s youth and beauty and so imprisons the younger goddess in her cave on Ben Nevis. Aengus dreams of Bride, falling in love with her, and he borrows three days from summer to put the Cailleach to sleep. He rescues Bride and they flee across the land, bringing spring in their wake. The Cailleach wakes and chases them, which is why we have a false spring, often followed by blustery weather in March and April.

As much as I loved this myth as a way of understanding and explaining the seasons, it never sat quite right with me. In other tales, Bride is not a meek princess who would weep and wait for a man to come and rescue her and the Cailleach is powerful and fierce – unlikely to be so jealous of another’s beauty that she would resort to such measures. In fact, in many versions of the Cailleach’s story, she is said to grow young and beautiful over the course of winter, only to age again during the summer.

I began to wonder what this story would look like if the two women were not placed in opposition to each other. I thought about what the myth I was familiar with told us, not about the gods themselves, but about the people who wrote it down. The Cailleach is jealous of another’s youth and beauty because we imagine aging beyond attractiveness to men as being the worst thing that can happen to a woman, but what if it’s not? Wouldn’t it be far worse to have your value and contribution constantly overlooked? Bride is meek and mild and obedient because those were virtues that were valued in a wife, but what if she was strong? What if she was determined to have power over her own life?

Was it possible to keep the exploration of the seasons and what they mean to people, while honouring the gods as I saw them? The Heart of Winter is my attempt to do just that. I’ll leave it up to the reader to decide whether or not I achieved my aim.

https://www.flametreepublishing.com/the-heart-of-winter-isbn-9781787588318.html

Scottish fantasy author Shona Kinsella is the author of The Heart of Winter, The Vessel of KalaDene series, dark Scottish fantasy novella Petra MacDonald and the Queen of the Fae, British Fantasy Award shortlisted industrial novella The Flame and the Flood, and non-fiction Outlander and the Real Jacobites: Scotland’s Fight for the Stuarts. Her short fiction can be found in various magazines and anthologies. She served as editor of the British Fantasy Society’s fiction publication, BFS Horizons for four years and is now the Chair of the British Fantasy Society.

Shona lives near the picturesque banks of Loch Lomond with her husband and three children. She enjoys reading, nature walks, and spending time with her family. When she is not writing, doing laundry, or wrangling children, she can usually be found with her nose in a book.

overhung by oak branches

Thinking about the lenses we use to view history

We went to the Earth Trust/Dig Ventures festival of discovery on Sunday. We listened to two talks by teams of young, enthusiastic archaeologists discussing the finds from digs around Wittenham Clumps. One was on everyday objects, and the other was on ancient animals. In between, we had a very nice lunch, strolled around the local landscape, and went to the pop-up museum where a small selection of the thousands of finds was on display.

I expect many of us have seen Roman tiles with cat and dog prints left when the clay was still wet. This is the first time I’ve seen a fox leave its mark.

Then there were the mystery objects, such as this. I always ask Husband what he thinks. After studying it for a few moments, he proposed a use that one of the archaeologists confirmed is their experts’ current best guess.

Apparently a feature of Bronze Age sites is ‘pots in pits’, and there’s much discussion about what deliberate deposits of selected items might mean. Rituals linked to ‘end of use’ are generally proposed, though it’s impossible to know whether these marked, for example, a death, the demolition of a dwelling, or moving away from an area. One such pit here is particularly interesting as the objects deposited are a well-used, smashed pot, broken loom weights and a 4 year old sheep. When swords and other weapons are deposited in water or pits, they are deliberately broken to put them beyond use. Is this a similar ritual involving objects associated with textile production? Sheep for meat were usually slaughtered by the end of their second year. Beyond that, they were primarily kept for wool. What does this tell us about spinning and weaving and those who did it? That these women and their skills were respected with such rituals? What does that tell us about these ancient people and their society? Maybe it wasn’t all mighty-thewed warlords defending helpless women and children?

Another speaker observed that ‘hillfort’ is increasingly considered a misnomer for enclosures ringed with ditches and banks, as modern archaeology increasingly indicates they weren’t built for defence, not primarily at least. People could retreat into them at need, but for most people, most of the time, these appear to be trading and gathering centres, possibly seats of power for tribal leaders. Where did the people come from to trade and meet? DNA work on burials on this site is still pending, but at least two skeletons have been interpreted by bone experts as likely of African heritage.

This got me thinking about where that term ‘hillfort’ had come from. Field archaeology pioneers from the 1850s onwards started surveying and excavating these landscapes. The British Empire was at war with someone or other through most decades of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. How much did that background noise of perpetual conflict influence these men to see such earthworks as military and defensive? What assumptions followed? You only build defences when there’s an enemy out there. Therefore anyone new must be an invader! But what if that initial assumption is wrong? The the whole framework collapses. Finds that have been interpreted to fit that world view should be reassessed. This is just one reason why I find current archaeology so fascinating.

Since one of my personal lenses for viewing history is its use in world-building for fantasy writers, it’s apt that the next creative writing article from my archive is on this very topic.

The Uses of History in Fantasy

Want something good to read in SF&F? Check out award nominations.

It’s always worth taking a look at the novels long- and shortlisted for genre awards – even if you’re not a member of organisations like the BSFA, the BFS, or SFWA. Likewise, it doesn’t matter if you’re eligible or not to vote for awards linked to conventions such as the Hugos. These are books that have appealed to a solid number of well-read SF&F fans. The juries who pick the winners for accolades such as the Arthur C Clarke Award and the World Fantasy Awards are fans first and foremost, and assess all submissions diligently. Not every book is for every reader, but there’s every chance you’ll find something to your particular taste that you haven’t come across before.

Then there are the short stories, the novellas, the non-fiction and related works. The odds are good that these lists will offer you unfamiliar names whose writing you’ll want to check out, both of authors currently published and of authors being written about. There’ll be discussions about aspects of the genre which you may very well find of interest. When something on any of these lists comes from a small press you haven’t previously encountered, it’s definitely worth seeing what else they’re publishing. And don’t forget the art awards, which invariably illustrate the breadth and depth of skill enhancing SF&F stories these days.

Why am I mentioning this now? Because the BSFA long lists have just been announced, and yes, I have an interest to declare because The Green Man’s Quarry is among the nominations for best novel. Will it be shortlisted? Who knows? At the moment, knowing enough readers enjoyed Dan Mackmain’s latest to nominate the book gives me a nice, warm feeling on this chilly wintry day.

If you are eligible to vote, but haven’t read this latest in the series yet, this is great timing, as the ebook is currently a Kindle UK limited time deal for the bargain price of 99p – and so are a good few other BSFA longlisted titles. Amazon have a wide-ranging SF&Fantasy offer on at the moment. That’s well worth checking out whether or not you’re interested in voting for any awards at all.

Happy reading!

What do you mean, it’s July?! An update…

Time flies when you’re busy! What have I been doing? First and foremost, I am very pleased to report that this year’s Green Man book is currently being honed and polished with the invaluable input of Editor Toby.

My next major task will be reviewing twenty-plus years of my short fiction to choose the stories for a collection to be published by NewCon Press, as part of their new Polestars series. I am tremendously honoured to be invited to be part of this, as you will see from the list of authors involved. The first three volumes are now available.

My Arthurian novel, The Cleaving, is being very well received, and I’ve written a couple of pieces about my thinking as I wrote this female-centered take on the classic myth. Sarah Ash will host the first of those on her blog tomorrow, and the second will be my contribution to the Fantasy Hive’s Women in Fantasy Month – where you’ll find all sorts of fascinating posts. This makes the Kindle offer on the ebook very timely. Until 14th July you can snap that up at a bargain price – £0.79 UK, €0.79 Fr, $1.99 US, $1.99 CAN, and I believe there are comparable discounts elsewhere. Check your local store.

The last couple of months haven’t all been work. I took a day off yesterday to see the Labyrinth exhibition at the Ashmolean museum in Oxford. This is about Crete, Knossos, the Minotaur and such. The Ashmolean and the Bodleian Library have lots of stuff about Arthur Evans and his excavations to share, as well as exhibits looking at the Minotaur and the Labyrinth as cultural images and ideas through the ages.

These include a video installation from Ubisoft showing a character going into the ruins of Knossos in Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey with a written commentary track highlighting the research they did into the site, the archaeology, and the classical literary references to the Minotaur in their monster concept. I think this is very cool.

Then there the little ceramic figures of what are reckoned to be priestesses in ornate headdresses doing some sort of snake ritual. The card earnestly told us that while a cat had been found buried where these figures were found, it’s not believed that the ritual was actually conducted with a cat sitting on someone’s head. Personally, thinking of some cats I’ve known, let’s not be so hasty…

A week to go to The Cleaving – links round-up

This time next week, The Cleaving will be published. The Angry Robot team are doing splendid work spreading the word – Caroline and Amy are absolute stars.

Click here to pre-order the ebook or the paperback direct from Angry Robot.

Over at Lithub, Natalie Zutter includes The Cleaving in her recommendations for some spring reading, alongside books from Peter S Beagle, Emily Tesh, Fonda Lee, Vivian Shaw, Andrea Stewart, TJ Klune, and Catherynne M Valente.

“Juliet E. McKenna retells the familiar Arthuriana epic through the eyes of enchantress Nimue, who possesses the same magic as Merlin but has more scruples than he does about interfering in mortal lives. So while Merlin helps Uther Pendragon trick the lady Ygraine into conceiving Arthur, Nimue is by Ygraine’s side, disguised as her handmaiden.

While the saga’s familiar male characters—Merlin, Uther, Arthur, Lancelot, Mordred—make their big moves through the rhythms of war, The Cleaving focuses on the women’s work and equally vital intrigues back at court. When Arthur’s half-sister Morgana and future wife Guinevere are brought into the mix, Nimue’s interactions with each provide additional context as to why both women make such dangerous choices that will eventually spell the fall of Camelot.”

I’ve mentioned the various interesting and enjoyable podcast chats I’ve had recently, and you can now listen to a couple of those conversations at the following places.

And here’s where you can find me in person over the next little while.

Diary updates – BFS Event 18th Feb, and more!

It’s all go at the moment, and in the best way. This coming Saturday 18th February, I’ll be taking part in the British Fantasy Society’s online February event. I’ll be on a panel at 1.45pm GMT discussing Hard vs Soft Magic Systems, with LR Lam and Steve McHugh.

Before that, at 1.30 I’m on the Author Readings schedule when I’ll be reading from The Cleaving for the very first time anywhere.

There’s a whole roster of great writers reading through the day, plus another panel on approaches to world-building, and an interview with Adrian Tchaikovsky, who is always worth listening to. You can find out full details and more besides on the BFS News page – click here.

On 14th March, I’m on a panel for the Society of Authors At Home event, discussing making a living from writing with children’s author Abie Longstaff and poet Katrina Naomi, chaired by Vanessa Fox O’Loughlin (also known as the crime writer Sam Blake). This will be a reprise of our very successful event at last year’s London Book Fair where we lay out the realities of the book business and suggest ways to maximise your earning opportunities. Full details here – and like all online SoA events (apart from the AGM) this will be open to members and non-members alike.

I’m also having a lot of fun recording some interviews this week, with the Fantasy Fellowship for their YouTube channel, and for the Read Write podcast. I’ll post links when those are available for you to enjoy.

And there’s more to come!

Recent reading and an online interview

The ongoing Twitter fiasco makes it harder and harder for authors to connect with readers in the ways we – and publishers – have come to rely on. So please share your enthusiasm for recent books you’ve enjoyed on whatever social media you use. Whatever the route, word of mouth recommendations sell books and those sales keep writers writing.

Another response seems to be a revival in blogging. Not that it ever went away. I’ve had the opportunity to answer some interesting questions from The Big Bearded Bookseller and you can read that interview with a click here. Readers, writers and illustrators as well as booksellers should definitely be aware of this website which offers a wealth of information.

I will now do my bit with a review of The City Revealed by Juliet Kemp, published by Elsewhen Press. The hardback and ebook are out and the paperback is published on 20th February.

I can’t recall if I’ve ever reviewed the fourth book in a series without having read the others. Why do that now? Well, I find Juliet Kemp an interesting writer to talk to, and I’ve liked what I’ve seen of their work. So when they offered me an advance copy of their forthcoming novel I was quick to say yes. Obviously, I could have gone and read the previous ‘Marek’ books first – The Deep and Shining Dark, Shadow and Storm, and The Rising Flood, but I decided not to. One of the serious tests for an author writing the next book in a series, is not demanding a reread of what’s gone before. I’m pleased to report that Kemp more than meets this challenge with unobtrusive recap which reads as naturally as backstory in a first volume.

The city of Marek faces multiple challenges. Declaring independence from the neighbouring ruling power hasn’t gone down well with those erstwhile overlords. Whose will now hold the highest authority in the city itself is hotly debated, and not only among the powerful Houses of the ruling Council. The Guilds are determined to have their say, while other factions in the wider population have plenty to say about the Guilds. There are different schools of thought on the different schools of magic which come with various limits and costs. When it comes to sorcery, what some see as opportunity, others see as threat. But magic is central to the city’s defences, and there’s every reason to expect an attack.

Marcia, House Fereno representative on the Council, is trying to handle all these things at once, while she’s in the final weeks of a pregnancy. She still has to work out how she’s going to co-parent the baby with her friend and sometime lover Andreas while sustaining her relationship with her girlfriend Reb. Just to make life that bit more complicated, Reb’s a sorcerer. This is one of a range of relationships among the characters, along with varied expressions of gender and sexuality. Why? Because that’s simply how life is in this particular fantasy world and it’s not the world we live in. This facet of the book shows how far epic fantasy has come since the days of white knights rescuing damsels in distress. Other aspects of Kemp’s world-building have moved on from such default settings. There are guns and broadsheets and the complexities of trade and geography, all conveyed with a deft touch.

At the same time, Kemp understands and shares the fascination with the core themes which have sustained this genre for so long. We see different characters’ responses to change and upheaval. We see tensions between moderates and radicals, and the struggles of those longing for progress with those who seek security in the status quo. Some people look for allies, others only want personal advantage. Others just want to shut their eyes and hope it all goes away. Kemp makes these people solidly believable, in their flaws as well as their strengths, through well-written dialogue and convincing interactions. Readers will care about these characters, even when some miscalculation leaves us wanting to shake someone till their teeth rattle. This makes for an eminently satisfying narrative where the personal, the political and the magical are multilayered and interlocked. A book – and a series – well worth checking out.

Silver for Silence – a new Philocles story for a very good cause

Regular readers will recall me flagging up the Books on the Hill project last year, aiming to publish quick reads specifically intended for dyslexic adults, to encourage them to explore and enjoy the great range of fiction available these days. I wrote about that here.

I’m delighted to say the initiative has been a great success! Alistair and Chloe are running a second Kickstarter this year, offering another tremendous selection of stories to give readers a taste of different genres. You can find Open Dyslexia: The Sequel here. You will note that names from the bestseller lists and TV adaptations such as Bernard Cornwell and Peter James are supporting this splendid initiative. I was naturally most honoured when Alistair asked me – or rather, my alter ego JM Alvey – to write a short history mystery (12,000 words) for this year’s line-up.

What you may well not know – because I certainly didn’t, and yes, I am embarrassed by my ignorance – is that making a read dyslexia-friendly is a case of formatting and layout and similar. For an author, the writing process is exactly the same. I’m aiming to challenge, entertain and intrigue with this new Philocles short story in the same way that I do with anything I see published. The only difference is more people will be able to read it – and I love the thought of that.

This project really highlights how much new technologies can do to make books more accessible for people with dyslexia. And that makes the absence of such initiatives by the mass-market publishers glaringly obvious. The book trade needs to take a long hard look at this situation.