Category: Publishing & the Book Trade

An October update in this year of treading water…

I was talking to one of my sons, and I commented that life felt stuck in an endless holding pattern these days. He likened it to treading water, and the more I think about that, the more apt it feels. Repetitive activity that gets tiring without actually moving on, and no sense of solid ground under your feet.

Thank goodness for things to break up the monotony!

First up, the Irish National SF Convention Octocon is happening online this weekend. Participation is free and should be a lot of fun! At 1pm on Saturday, you can join me and other writers discussing the uses of myth in our work and I’ll also be doing a reading at 4.30 pm on Saturday. You can see how much longer my hair is now…

Next week, the 15th October, sees the publication of my alter-ego’s third murder mystery set in classical Athens. Philocles is looking forward to the Great Panathenaia – until one of the poets due to take part in the dramatic performance of Homer’s Iliad is brutally murdered. The authorities want this cleared up quickly and quietly. Philocles finds himself on the trail of a killer once more…

You can find out more here, including preorder links. If you do NetGalley, you can find it there.

In other unsurprising news, publication dates and acquisitions continue to be delayed and pushed back as the book trade continues to try to navigate the current chaos with varying consequences for writers. Those books that do reach the shops – bricks and mortar or online – have to compete in a scrum where the big names and lead titles are getting pretty much all the promotion and shelf space. I think we’re going to see the shift to independent and smaller press publishing accelerate, with greater online engagement direct between writers and readers. I’m seeing more Patreons and Kickstarters appear, alongside a growing realisation from fans that these are an increasingly good way to get the books they want.

As for my own work, The Green Man’s Silence is selling well, and gathering very good ratings and reviews. I’m extremely grateful to everyone who is sharing their enthusiasm for this, and the previous books. Thank you all. I am getting some ideas together for Dan’s next adventure… and I have a couple of short fiction pieces to write, as well as a few other things to do. Then there’s the shared world novella I wrote earlier this year – as soon as I have a release date, I’ll share it.

I’m also amused by a recent review of The Green Man’s Foe, where the reader includes the very minor spoiler that THE DOG DOESN’T DIE. To be clear here, I’m not making fun – when these things matter to a reader, they matter, and it’s not for anyone else to say they should feel different. Thankfully, this reader enjoyed the book, even though they found their concern over the dog’s fate distracting. All I can say is, hand on heart, it never occurred to me to put the dog in danger!

Problematic issues re Amazon reviews

Whatever social media you use, you doubtless see regular polite/pleading reminders from your favourite authors about how important online reviews are these days, and reviews on Amazon most of all.

This isn’t just needy writers looking for some ego boost. Publishers tell us authors time and again how reviews drive vital visibility when their numbers reach the ever-shifting tipping points that trigger different promotional algorithms. How even readers who don’t shop at Amazon use the site to see what other people think of books that interest them, as they decide to buy. How publishers can even use a title’s level of reviews as one measure of a writer’s popularity and a possible predictor (among others) of interest in a possible future project.

So please support your favourite authors with Amazon reviews. As long as you are allowed to. This is where all this starts to get problematic. A pal thought to do me a favour by leaving a genuinely favourable review on Amazon only to have it rejected because their spend on the site over the last six months didn’t reach the required threshold. I went to see what was what and found this on Amazon UK –

“To contribute to Community Features (for example, Customer Reviews, Customer Answers), you must have spent at least £40 on Amazon.co.uk using a valid payment card in the past 12 months. Promotional discounts don’t qualify towards the £40 minimum.”

Since I remarked on this on social media, various other people have confirmed that the same thing had happened to them. Though what that qualifying spend might be clearly varies from time to time and place to place. That doesn’t surprise me. We already know that Amazon regularly tweaks their algorithms’ review number trigger points as they look for the best way to maximise their revenue. Other things also became apparent. You don’t have to be buying books to qualify, just stuff, because this isn’t about books, it’s about Amazon making money. Indeed, when some people found they were unable to post reviews they were told that their Kindle purchases didn’t count because the spend had to be on physical goods. Whether or not an Amazon Prime subscription counts seems to vary as well.

Why are Amazon doing this? The obvious answer is it’s a countermeasure against bots and review spam. That’s fair enough, but it’s a very, very blunt instrument. It does nothing to stop astroturfing (faking ‘grassroots’ support) by someone with a lot of pals who buy sufficient stuff online. But that’s not Amazon’s concern. They’re in business to make money, first last and always.

So what can we do? Well, the reason that reviews matter is what sells books is word of mouth recommendation. That’s been the case for ever. All the Internet has done has enabled us to tell each other about a good new book in a whole lot of new ways. So carry on doing that – but now, please try to remember to look beyond Amazon when you want to support an author by boosting a book and when you’re looking for recommendations. If you have the time and inclination, check out Goodreads maybe, and/or look for the bookbloggers that share your particular interests.

Whatever social media you use, whenever you can spare the time for a quick mention, even just a line or so, it all adds up and it all helps to boost the signal, and that’ll help keep your favourite authors writing. Thanks.

A few thoughts on literary agents.

There’s a thing going around on Twitter, from a US small press saying that they only work with unagented writers now, and any agented writers they accept will be required to drop the aforementioned agent.

My guess is this outfit want to tap into the ‘real indie authors go it alone and stick it to The Man by making a fortune’ mythology that never mentions the millions of writers with shattered dreams to set against the very few high-profile successes.

Meanwhile, back in the real world, this is a huge red flag, as umpteen people have pointed out, and has more usefully, started conversations about literary agents.

Are they essential? No. Are they extremely useful? Most definitely. Are the majority of writers well-advised to work with one? Absolutely. This is one reason why publishers who take on unagented writers usually recommend they get an agent at that point. It works out best for everyone in the long run, in most cases.

I did my first deal without an agent but I knew a fair bit about contract law from a professional qualification, plus I had back up from The Society of Authors. Anyone with a contract offer should get advice from them or a similar professional body.

In passing, I’ll just mention that I walked away from a publishing contract I was offered about a year ago, when SoA advice confirmed my misgivings. It was a perfectly legal and legit offer – but a lousy one in terms of who would earn what, and the backing the book could expect. If you’re working unagented, you need to be ready to walk away.

Back in 1997 I replied to that first offer letter/contract with 3 pages of clauses to add, clauses to amend and clauses to strike. This is not typical debut author behaviour. This is where most new writers find having an agent is essential, because if publishers can get away with minimising their obligations, they will. This is business and authors need to understand that. Agents do understand that, and that’s why reputable publishers are happy to work with them.

As my career progressed, I got a literary agent to handle all the more complex stuff like foreign rights etc to free up my time to write. That decision earned me far more than paying the agent’s commission cost me. It’s good business sense.

Over the past twenty years, I’ve worked succesfully without an agent and with different agents, as has suited me at the time. That has always been my choice. I will never work with a publisher who insists I drop an agent. There can be no good reason for that.

Yes, there are crooks and charlatans out there calling themselves literary agents, just like crooks and charlatans calling themselves publishers, Authors must always do their research and be alert for scams or bad deals. That’s a different conversation.

Thoughts on writing and publishing, from me and others.

I’ve had a productive week writing and while I’ve been doing that, a couple of guest posts by me have appeared elsewhere.

Marie Brennan is asking various authors about that moment when a book idea really ignites. This Must Be Kept A Secret is my contribution to her ongoing Spark of Life blog series, looking at the rather different experience I had with Shadow Histories, compared to the Einarinn novels. Incidentally, if you haven’t already come across Marie’s ‘Lady Trent’ books, do take a look. I adore them.

In other writing related posts I’ve spotted this week

Fantasy Author Robin Hobb on Saying Goodbye to Beloved Characters and Those GRRM Comparisons

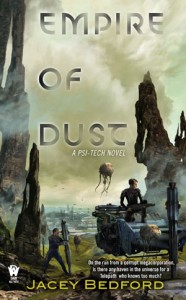

Jacey Bedford on writing and being edited from the writer’s perspective. Another writer whose books you should check out.

Looking at the business side of the book trade, I wrote a guest post for Sarah Ash’s blog. The Bugbear of the ‘Breakout Book’ for Readers and Writers alike – Juliet E. McKenna

I also noted this piece by Danuta Kean – not another ‘self-publish and get rich quick’ piece but an interesting look at another facet of the changing book trade, including the pitfalls for the naive author. ‘Show me the money!’: the self-published authors being snapped up by Hollywood

Okay, that should keep you in tea or coffee break reading to be going on with.

Andrew Marr’s Paperback Heroes – a masculine view of epic fantasy entrenching bias.

Two things happened on Monday 24th October. News of Sheri S Tepper’s death spread – and a lot of people on social media wondered why isn’t her brilliant, innovative and challenging science fiction and fantasy writing better known?

Then the BBC broadcast the second episode of Andrew Marr’s series on popular fiction, looking at epic fantasy.

The programme featured discussion of the work of seven, perhaps eight, major writers – six men and one, perhaps two women if you include the very passing reference to J K Rowling .

Four male writers were interviewed and one woman. Please note that the woman was interviewed solely in the context of fantasy written for children.

If you total up all the writers included, adding in cover shots or single-sentence name checks, eleven men get a look-in, compared to six women. Of those women, three got no more than a name check and one got no more than a screenshot of a single book.

It was an interesting programme, if simplistic in its view, to my mind. There’s a lot of fantasy written nowadays that goes beyond the old Hero’s Journey template. There’s a great deal to the genre today that isn’t the male-dominated grimdarkery which this programme implied is currently the be-all and end-all of the genre.

But of course, I can hear the justifications already. A general interest programme like this one isn’t for the dedicated fans, still less working writers like me. For mass appeal it must feature authors whom people outside genre circles have heard of, and whose books they’ll see in the shops. If these books just happen to be mostly written by men, well, that’s just the way it is.

Am I saying these aren’t good books which have a well-deserved place in the genre’s origins and evolution? No, of course I’m not. All these featured and interviewed writers are deservedly popular, their books widely read, and their work is illustrative of points well worth making about fantasy.

But those same points could have been made just as effectively while featuring a more balanced selection of writers, from the genre’s origins to the present day. So what if that means including less familiar names? Do you honestly think readers interested enough to watch a programme like this will object to discovering a new author to enjoy?

When such a programme has a marked gender skew, it matters. This selection guarantees these are the books that’ll get a sales boost from this high-level exposure. So when the next programme maker comes along to see what’s popular, maybe with a view to a dramatisation or to feature in a documentary, he’ll see that same male-dominated landscape. So that’s the selection of books that will get the next chance of mainstream exposure. Thus the self-fulfilling prophecy of promoting what sells, thereby guaranteeing that’s what sells best, continues to entrench gender bias.

If you’re wondering how the work of writers like Sheri S Tepper and so many other ground-breaking women writers is so persistently overlooked, you need look no further than programmes likes this.

(For more – lots more – on equality issues within SF&F, click here)

Why Golden Age crime writers banned ‘The Chinaman’ and other notes.

I spent the past weekend at the annual St Hilda’s Mystery and Crime Conference, and as always, came away with a broad range of interesting notes and thought-provoking questions. This year, the papers explored the question of genre: asking just what is crime fiction? So here are just a few things that came up, necessarily in brief.

The conference opens on Friday evening with drinks, a dinner and a guest speaker. This year that was Ted Childs, the TV producer who brought ‘Morse’ to the small screen. It was fascinating to hear how that all came about, back in the day when ITV was still very much a collection of regional broadcasters. As well as an affectionate and nostalgic reminder of John Thaw’s talents, among others, his talk was also a reminder of just how ground-breaking the production was back then; two hour episodes on film rather than video, recruiting writers and directors from stage and movie backgrounds. Without Morse, it’s fair to say the TV landscape of today would look very different, and not just for detective dramas.

On Saturday morning, Elly Griffiths looked at the changes in domestic life, particularly domestic interiors from the Regency to the Victorian era when crime fiction first emerged. As her slides showed, the Victorians surrounded themselves with stuff in a way their forebears never had. In this age of uncertainty, as science challenged religious certainty, as new philosophies challenged political certainties, the home became a sanctuary, filled with all this stuff holding emotional resonance and value of its own. Thus invasion of this home, in an age that could feel so threatening, becomes all the more shocking and transgressive? The home itself could become claustrophobic and tyrannical, provoking extreme acts and emotions. There’s a lot to think about there.

Jane Finnis proposed various lines to be drawn between fairy tales and crime fiction and not just the restorative justice aspects, though that is certainly important. Consider how many fairy tales involve looking for clues and solving a puzzle. Once you start looking, you can find a lot of fairy tale themes that crime fiction has retold, reinterpreted and developed for the modern, mass-reading audience. Issues of trust, deception and self-reliance. Then there’s the formula of ‘a long time ago, in a land far far away’ which removes the threat, the abominable acts, the violent retribution, to a safe distance while still allowing the reader to see the value of using one’s wits and challenging evil. Consider how many people who read mystery fiction really do not like true crime writing and how many writers feel uneasy about drawing too closely on real atrocities and tragedies. ‘Far too close to home’ is a telling phrase.

This was of particular interest to me given I’m increasingly convinced that folklore and fairy tales are an undervalued precursor to epic fantasy fiction in its current form. Especially when you look back to the original tales as collected by Grimm, Perrault etc, rather than their subsequent sanitised forms. Where, incidentally, female characters can have a lot more agency than later versions allow them, as was remarked on at the weekend.

Conference Guest of Honour Lee Child went even further back. He proposed the thriller as the original fiction that everything else has stemmed from, thanks to its original evolutionary purpose. If you want to know more, you’ll be pleased to know that this was livestreamed at the time and you can watch the recording here.

And all that was just Saturday morning! After lunch, Martin Edwards looked at the resurgent interest in and fashionability of Golden Age crime fiction – principally those books published between the World Wars. He’s involved in the wonderful British Library Crime Classics now being republished, editing their anthologies and consulting on the series as a whole. A closer look at those writers, their themes and their villains does give the lie to the ‘snobbery with violence’, ‘Downton Malice’ interpretation based on partial knowledge of Christie, Sayers, Allingham et al. He drew on a good few parallels with concerns then and those of our own times, most notably distrust and disillusion with politicians and rapacious money men as villains and unsympathetic victims. Carol Westron explored the various ‘Rules’ for detective fiction that contemporary writers produced back then and once again, closer examination shows that the genre writing of that era was considerably more complex than a glance at these supposed guidelines might suggest. Most of the successful writers broke them wholesale.

Something both speakers touched on was the ‘No Chinamen!’ dictum of the time, which can and has been held up as a symptom of that era’s endemic racism polluting crime fiction. Except… looking at contemporary discussions of that point, a great many more interesting angles arise. ‘The Yellow Peril’ was the bogeyman of the age, to such an extent that at one point, no fewer than five West End plays in production were blatantly sinophobic, not to mention the on-going hostility and shock-horror stories about ‘orientals’ in the popular press. Genre commentary at the time warned crime writers off pandering to such ill-judged and unsubstantiated prejudice – and of the dangers of bad writing in doing so – by so lazily seizing on the villain of the moment. The parallels with contemporary islamophobia are striking. Of course, views on race and ethnicity nearly a century ago remain a world away from our own but this is a salutary reminder that the past is a good deal more nuanced than we might be tempted to think.

Further papers looked at the development of various sub-genres within crime and mystery fiction, from past to present. Andrew Taylor looked at historical fiction, while Shona MacLean considered the challenges of writing such books from the professional historian’s viewpoint. Kate Charles reviewed the origins and growth of clerical detectives as a niche while Chris Ewan looked at humorous crime fiction. Sarah Weinman reviewed the originators of domestic suspense – because these books were being written decades before the current slew of ‘Girl in/on/who’ best-seller titles as the ‘Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives’ collections make very clear. Lastly but by no means least, Marcia Talley looked at murder least foul – the ‘cosy’.

I can’t attempt to summarise these papers as they were all wide-ranging and came with copious examples of writers laying the ground work for such varied writing as far back as the 20s and 30s. Many of them were women asking questions of women, which has now somehow been airbrushed out of popular memory. Looking at the ways in which each sub-genre is still reflecting and testing the core tenets of crime fiction, its central themes and archetypes was and will continue to be fascinating for me.

The frequently under-estimated skills required were mentioned more than once. The challenge of making historical characters both of their time and accessible to modern readers is significant. Using humour not to make light of the awful reality of murder but for example, to hold up the corrupt to ridicule alongside grim events, is no easy trick. Similarly there’s considerable craft in achieving the necessary suspension of disbelief to make an amateur sleuth work in this day and age without tipping over into the ridiculous. And given the protagonists and primary market for cosy mysteries are mostly women, it’s hard not to conclude there’s quite some misogyny in the disdain those books so often attract.

Regular readers here will be seeing the echoes and correspondences with ongoing debates within SF&Fantasy that I did. I found many of the same concerns we have about our own genre with regard to retail and publishing trends. This is primarily a conference about the fiction but you won’t be surprised to learn I had a few shop-talk conversations with other authors. Publisher mergers and restructuring have caused similar carnage of late, especially among the mid-list. Editorial decisions seem to be driven by marketing and retail assumptions based on highly debatable reasoning about what will or will not sell, with scant consultation of actual readers. Frustrating levels of risk-averseness were mentioned, all infuriatingly familiar.

But I shall try not to dwell on that. Instead, I shall start working my way through the list of authors and titles now added to my To Be Read List. Thanks to the magic of ebooks I can do a bit of that this week and next as I am currently in Holland, thanks to the demands of my Husband’s work colliding with our holiday plans and seeing us both head out here a week earlier than our planned trip to the Ardennes. So bear in mind I’m only going to be online intermittently – I’ll be very interested in your observations in comments here but won’t be replying or answering questions in a particularly timely fashion.

Do raise a hand in comments or somewhere online if you’re interested in details of next year’s conference. Then I can pass on the information as soon as I get it.

Brief thoughts on women writers being erased from SFF – again

Another day, another article* supposedly assessing the cutting edge of Science Fiction written over the decades. Citing twenty five authors. All men. No, I’m not going to link. You can find it for yourself at SF Signal if you really want to. Or whatever particular piece has prompted me to repost this.

Like every other such article, it hands women writers a poisonous choice. We can object, with all the hassles and loss of our own working time which that will entail, as the usual counter-objections come straight back at us. That’s best case. Worst case? The full gamut of ugly insults and threats.

Or we can let the erasure stand, damaging women in SF&F, present and future.

Either way, we lose out.

I can easily predict the ways an objection to this particular piece will be dismissed. “It’s taking the long view and since men have dominated historically, the list will inevitably skew male. There’s nothing to be done about that.”

Yes, there is. Research. Start with Octavia Butler – and while you’re there, make a note that erasing writers of colour and those of differing sexuality is equally damaging and yes, just as dishonest.

Then there will be the expressions of concern – some even genuinely meant. “It’s just one article. Does it really matter?”

No, it isn’t just one article. Stuff like this crosses my radar if not weekly, at least once a fortnight. And that’s without me making any effort to find it.

As an epic fantasy writer, I’m just waiting for the first instance of that now well-established harbinger of Spring. The article saying “Game of Thrones will be back on the telly soon. Here’s a list of other authors you might like (who just happen to all be men).”

And if I object to those? “Oh, don’t take it so personally.”

No, women SFF writers don’t take these best-of lists, these recommended-for-award-nominations and shortlists, these articles and review columns erasing us ‘personally’.

We object because they damage us all professionally.

More than that, erasing women authors impoverishes SF&Fantasy for everyone by limiting readers’ awareness and choices today and by discouraging potential future writers

Which is why this matters.

Every

Single

Time

Right, I have work to do, so I will go and do that. If you want read further thoughts on all this, check out Equality in SF&F – Collected Writing

*I did start adding the dates and reasons every time I reposted this but I’ve had to stop as the list was pushing the actual article off the bottom of the screen… which tells its own tale really.

Guest Post – Jacey Bedford on whether she writes SF or F?

As I’ve mentioned previously, I’m very much enjoying Jacey Bedford’s Psi-Tech novels, namely Empire of Dust and Crossways, which are thoroughly good space-opera ticking all the boxes that first made me love SF while also thoroughly satisfying to me as a contemporary reader. So I was both startled and intrigued to learn that her new book, Winterwood, is a historical fantasy, set around 1800, with pirates and spies and mysterious otherworldly creatures all entangling Rossalinde Sumner in their machinations. You won’t be surprised to learn I invited Jacey to tell us all about that, and she has generously obliged.

SF or F? Trying to work out the differences and similarities.

With Winterwood, the first book of the Rowankind Series, on the brink of publication, Juliet asked me to write about transitioning between writing science fiction and fantasy. I sat down to think about it, but the more I worked on the differences between the two, the more similarities I came up with.

For starters, from the outside it does look as if I made a switch in genres, but it’s not quite the way it looks from the inside. My first two books to be published. Empire of Dust (2014) and Crossways (2015), are science fiction/space opera, but it’s a quirk of the publishing industry that they came out first. Winterwood, my historical fantasy, was actually the first book I sold to DAW, back in 2013, but it was part of a three book deal. DAW’s publishing schedule was such that there was a gap in the science fiction schedule before the fantasy one, so Empire of Dust ended up being published first. The order of writing, however, was Empire, Winterwood, and Crossways.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Confused? I don’t blame you.

Let me backtrack. The road to publication is often slow and tortuous. Many of us who eventually make it have a drawer full of completed books before getting the magic offer from a publisher. These aren’t necessarily bad books or rejected ones, but ones that have not been on the right editor’s desk at the right time. The difference between a published writer and an unpublished one is often, simply, that the unpublished one gave up too soon. I started writing my first novel in the 1990s without any hope of finding a publisher, and with no knowledge of how to go about it, even if I’d been brave enough to try. That, however, was all about to change – mostly because of the internet. Once I got online in the mid 90s I connected with real writers via a usenet newsgroup called misc.writing, and learned all the basics about manuscript format and submission processes. (And yes, I’m still in touch with some of those very generous writers two decades later.) While all this was going on I finished a couple of novels and made my first short story sale.

The two early novels, at first glance, were second world fantasies, but the deeper I got into them the more I realised that they were actually set on a lost colony world. There are places where science fiction and fantasy cross over to such a degree that it’s hard to see where the boundary is. My lost colony world had telepathy but no magic. So thinking about it logically, how did that colony come to be lost? What put telepathic humans on to a planet and then kept them there, isolated from, and ignorant of, their origins?

That was the question that I started writing Empire of Dust to answer (though it may take all three Psi-Tech books to do it). Because the story involved planets, colonies and space-travel, I was suddenly writing science fiction. I don’t write hard, ideas-based SF. I’ve always been far more interested in how my characters’ minds work than what drives their rocketships, though I’ll always try to make the science sound plausible if I can.

Characterisation – that’s always the crux of the matter for me. Take interesting characters and put them into difficult situations and see what they do. It doesn’t actually matter whether they are in the past or the future, or even on a secondary world, what matters is that the characters grow and develop via the story to overcome problems and reach a satisfactory conclusion. Well, OK, the setting matters, but it’s not always the first thing that hits me. The setting and the detailed worldbuilding grows around the characters and weaves through the story, adding context and interest, and sometimes becoming a character in its own right.

So Empire of Dust, in a much earlier form, was finished in the late 90s and then began the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. Remember what I said about persistence? Well, I’m dogged, but not always very pushy. Empire sat on one editor’s desk at a major publishing house for three years after the editor in question had said: ‘The first couple of chapters look interesting. I’ll read it after Worldcon.’ It took me three years to figure out I should withdraw it and send it somewhere else. Then the next publishing house it went to took another fifteen months. Those kind of timescales can eat up a decade very quickly. (I know one author who took to sending her languishing submissions a birthday cake after a year.)

In the meantime I kept on writing. It just so happened that the next three books were fantasies unrelated to each other: a retelling of the Tam Lin story aimed at a YA audience; a fairly racy fantasy set in a world not dissimilar to the Baltic countries in the mid 1600s, and a children’s novel about magic and ponies (not magic ponies). Why fantasy? I think I instinctively wanted to widen the scope of what I was doing to take in a wide variety of settings, however it was still mainly dictated by the characters.

If story and character are a universal constant, surely the difference between writing science fiction and fantasy is all down to worldbuilding. Right? Uh, well, maybe…. Science fiction can (to a certain extent) be fuelled by handwavium based on the accumulated reader-knowledge of how SF works. SF readers have an idea of how physics can be bent without being completely broken, whether you’re talking about the physics of Star Trek (warp-drives, photon torpedoes), or the hard SF of Andy Weir’s The Martian (which I love, by the way). When you write fantasy, you don’t have Einstein to fall back on. You have to work out how your fantasy world works from the ground up. If there’s magic, the magic system has to be logical and not contradictory (unless you build in a reason for the contradictions). If it’s set on a secondary world you might have strange creatures, races other than human, or even gods who act upon the world or the characters. Though, come to think of it, aliens, strange flora and fauna, and even ineffable beings are obviously common to science fiction as well. And when I said fantasy doesn’t have Einstein to fall back on, it does have the accumulated folklore of several millennia to point the way.

I think I’ve just talked myself round in a circle. So far, so similar.

So I started my next project, Winterwood, around 2008. By this time Empire of Dust had had three near misses with major publishers, but was still doing the rounds.

Winterwood almost wrote itself. I had the first scene very firmly in my mind – the deathbed scene – a bitter confrontation between Ross and her estranged mother. I wrote it to find out more about the characters and their situation. Ross hasn’t seen her mother for close to seven years since she eloped with Will Tremayne, but now her mother is dying. About halfway through the scene Ross’ mother asks (about Will): ‘Is he with you?’ Ross replies: ‘He’s always with me,’ and then follows it up with a thought in her internal narrative: That wasn’t a lie. Will showed up at the most unlikely times, sometimes as nothing more than a whisper on the wind. That was an Ah-ha! moment. I realised that Will was a ghost. Ross was already a young widow. That led me deeper into the story and gave me another character, Will’s ghost – a jealous spirit, not quite his former self, but Ross is clinging to him because he’s all she has left. That sets the scene nicely for when another man finally enters Ross’ life, but the romance is only part of the story. Ross inherits a half-brother she didn’t know about, and task she doesn’t want – an enormous task with huge consequences. There are a lot of choices to be made, and no easy way to tell which are the right ones. Ross has friends and enemies, some magical and some human, but sometimes it’s difficult to tell them apart. Even her friends might get her killed.

When that first scene came into my head, it could have been set in any place, any time. Parents and their children have been disagreeing and falling out for as long as there have been parents and children and, I’m sure, until we decide to bring up all our offspring in anonymous nurseries, it will continue well into the future. Ross took shape as I wrote, and I realised it was set in the past, or a version of it. In her first incarnation Ross was a pirate rather than a privateer, but I wasn’t sure what historical period to set the book in. The golden age of piracy was really in the 1600s, but I wanted to set this slightly later, so I decided that 1800 was a good time to play with. It’s a fascinating period in history with the Napoleonic Wars about to kick off in earnest, Mad King George on the British throne, the industrial revolution, the question of slavery and abolition, and the Age of Enlightenment. Of course I added a few twists, like magic, the rowankind and a big bad villain, who is actually the hero of his own story, though that doesn’t make him any less dangerous to Ross.

Historical fantasy is yet another subset of F & SF. If you’re writing in a specific historical period, you can make changes to incorporate your fantasy elements, adding magic for instance, or tweak one historical, point, but then you have to make sure that there’s enough solid historical background to make the rest of it feel authentic. You’re not necessarily looking for truth, but you are hoping for verisimilitude. I’m an amateur historian, not an academic one, but I did a lot of research: reading, museums, studying old maps and contemporary photos. I have several pinterest boards devoted to visual research, costume (male and female), ships, transport and everyday objects. Whenever I find something interesting I pin it for later consideration.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

So where did we leave the publishing story? Oh, that’s right, Empire of Dust was doing the rounds of publishers’ slushpiles. While that was happening I submitted Winterwood to DAW and after about three months got that phone call that every unpublished author wants. Sheila Gilbert said: ‘I’d like to buy your book.’ One thing turned into another and before long I had a three book deal. As I said earlier, Sheila decided that Empire of Dust would be the first book out, even though it had been Winterwood that had initially grabbed her attention. Then she ordered a sequel to Empire, which was the book that became Crossways. If you want me to talk about writing a book to order, sometime, that would be another post altogether. Suffice it to say that Crossways came out in August 2015 and allowed me to take the stories of Cara and Ben to another level and move the setting from the colony planet to a huge, and vastly complex, space station, beautifully illustrated on the book’s cover by Stephan Martiniere.

Getting a book from writer to store shelf is a multi layered process. There’s the writing and then the edit – which usually means some rewriting with additions. The once the final story has been accepted as finished it goes through copy-editing where clunky prose and spelling mistakes are smoothed over, and in my case, my British English is translated into American. Once the copy edits have been done then next part that I’m involved in is the page proofing, the final check after the book has been put into its finished form. This is the last chance to catch typos and brainos, but there’s no real opportunity to make big changes.

During the various editing processes there are gaps while your editor reads and considers, or the copy editor does his or her thing, so you tend to be working on other stuff while you’re waiting. The beginning of one book overlaps the editing process on the previous one and will in turn be at the editing and copy-editing stage when you’re just beginning to write the book after that. So, you see, it’s not like you have the luxury of working on one book at a time. The whole process is plaited together, fantasy and science fiction running alongside each other.

Winterwood comes out on Tuesday 2nd February. I’m currently writing Silverwolf, its sequel, which is due out late 2016 or early 2017. After that I’m contracted to write a third Psi-Tech novel (the aforementioned Nimbus), so it’s back to another space opera to follow on from Empire of Dust and Crossways. After that I’d like to write a third Rowankind novel. I already have ideas and there will be a few loose ends at the conclusion of Silverwolf, though, don’t worry, I never leave books on cliffhangers.

So the transition between science fiction and fantasy is not neatly delineated. It’s all mushed up together in both my writing timeline and in my brain. On the whole I just write stories set in different worlds. Some of them happen to have rocket ships, and others have magic, but all of them have characters who have adventures, relationships, and make choices, good and bad. I’m happy hopping between the future and the past, and I’m super-happy that my publisher has given me the opportunity to be an author who writes both SF and F.

You can keep current with all Jacey’s news over at her website.

P.S I’ve just finished reading Winterwood and can recommend it as highly as the Psi-Tech Novels.

Are we finally seeing the long-overdue examination of what’s gone wrong with the book trade?

Philip Pullman and those writers backing him (referenced in my previous post) seem to have prompted an important – and to my mind, long overdue – examination of exactly what’s gone wrong with the book trade in the past five or ten years.

From Nick Cohen, on his experience of being asked to appear at The Oxford Literary Festival. ‘Why English writers accept being treated like dirt’

For those who don’t have time to read the whole thing just at the moment, the key quote for me is as follows:

If the system does not change, readers will suffer for a reason that cannot be repeated often enough. The expectation that workers will work for nothing is leading to the class cleansing of British culture. Everywhere you go, you hear culture managers saying they want ‘diversity’, while presiding over a culture that might have been designed to exclude the working and lower-middle classes. Whether you look at journalism, the arts, the BBC, photography, film, music, the stage, and literature, you see that those most likely to get a break are those whose parents are wealthy enough to subsidise them. The generalisation is not wholly true. Young people from modest backgrounds can still break through. But every year their struggle becomes a little harder. Every year, an artistic career becomes a little less viable to potentially talented writers and artists.

From Philip Gwyn Jones, laying bare the implications for readers. ‘The civil war for books; where is the money going?’

Though this post isn’t just about money. It’s about the ways changes in bookselling influence publishing decisions and ultimately limit readers’ choices. Once again, until you can find the time to read the whole thing.

as a commissioning editor and publisher of some 25 years standing, I hope I have some authority to make the claim that certain stars are missing. They are just not being born. It seems to me that there is a universe of self-censorship out there, even if it is invisible to the naked eye. We’ve had perhaps five years now of good writers taking their next ambitious project to their agent who in turn excitably puts it in front of publishers only to be told that it’s perhaps a little too bold an idea for these austere and shape-shifting times, and might there not be a more reader-friendly project up the writer’s sleeve? The agent sheepishly reports this back to their beloved writer, who then either conforms to the market’s demands or slopes away to nurse their wounded ego, and think hard about the purposes and pleasures of writing. The next time that writer comes up with a bold, unorthodox, unprecedented notion for a book, what happens? Well, perhaps, just perhaps, they decide before they start in earnest that it’s a no-hoper and they ought to play safe, so they bin it without telling anyone. And another bright star never shines.

…

Social reading is the coming thing, we are told, where our reading devices and apps will allow us to communicate with others who are reading the same book we are, share notes and queries with them, correct and conject, exult and excoriate together as if we online readers were round a digital dining table, and even involve the writer in that conversation if they are willing. But for such Social reading to work, everyone has to be reading the same thing, so it tends to favour the popular, the shared, the already-known. Hence the ubiquity of Most Read and Most Liked lists. There is a lot of barked coercion out there in cyberspace. So the online sharing book economy will coalesce around, well, winners. But what happens to the losers: the unshared, the jagged, inimitable, harder-to-chat books?

And the next time you’re in your local High Street or supermarket, take a look at the books on offer and I’m pretty sure you’ll see all these forces already at work.

Which incidentally, brings me back to something important about SF conventions and the genre small press. Both continue to support and promote writers and books outside the mainstream, thanks to the support of readers looking for something beyond mass market fodder.

Key differences between Literary Festivals and SF Conventions when it comes to payment

I’m extremely pleased to see Philip Pullman making a stand on the issue of literary festivals not paying writers – when everyone else involved gets paid – and to see a host of other authors backing him.

But I am also seeing a degree of confusion, particularly from SF&Fantasy fans/writers who think this is a call to pay programme participants at SF conventions. Some clarification may be useful. As well as regularly attending conventions, I’ve long been involved with non-genre literary festivals thanks to working with The Write Fantastic and also as a committee member for my old Oxford college’s Media Alumnae Network. Consequently I have observed how very different their approaches are.

Literary festivals organise their programming primarily around publishers’ schedules and offer one or two writers per slot an opportunity to publicise their current book. The biggest names with the highest media profiles get the biggest venues and the best time slots because these are commercially-minded enterprises whether or not they’re structured as charities like the Oxford Literary Festival. Everything from venues to publicity to technical support must be paid for and that means selling tickets to fill the seats. None of this is criticism. I always enjoy hearing a talented author share their enthusiasm for their work, fiction or non-fiction, as I sit in a quietly attentive audience. And yes, the big name events do help fund the lesser known and special interest authors’ events – such programming is assuredly valuable for readers and writers alike.

But make no mistake; this is work for an author. It’s essentially an hour’s professional performance or presentation. It’s just not treated as such. Over the years, as a contributor at assorted festivals, I’ve turned up, got a cup of coffee in the green room, done my thing, and that’s pretty much that. Depending on the time of day I might be offered access to a buffet lunch (problematic for anyone with dietary issues). I’ve generally had my travel expenses covered but in all but a very few cases, I haven’t been paid for my time on the day or for the essential preparation. And no, the royalties I might get from however many of my books are sold at the festival wouldn’t come anywhere close to a reasonable fee. I might get a ‘goody bag’ with something like a bottle of wine, maybe some perfume, and a couple of books (which alas, I seldom actually want). I would usually get one or two complimentary tickets for my own event, nice for friends and family, but if I want to go to any of the festival’s other events, I have to buy tickets like any other punter.

SF conventions are very different. From their earliest days, conventions have been fan-led events. Readers and writers alike are encouraged to get involved, exploring their shared enthusiasm. Those going to SF conventions pay for memberships rather than tickets. People aren’t buying a seat to passively attend a one hour event. They’re investing in the funding of a collective enterprise over several days, run by volunteers for fellow enthusiasts.

A weekend’s membership gives access to dozens, even hundreds of programme items. There are fact-based sessions, where fans and authors alike share their knowledge and expertise on everything from science in all its ramifications to historical, linguistic, political and psychological scholarship – just a few disciplines which underpin the ever-broadening scope of speculative fiction. As well as sessions exploring creative writing, programme items explore visual skills and disciplines from fine art providing inspiration to writers and artists alike, to comics and graphic novels. There’s discussion of SF and fantasy in film, TV and audio drama, from author and audience perspectives. Then there’s the fun programming, including but not limited to games and costuming events, ranging from the admirably serious to the enjoyably daft.

At a literary festival it’s rare to see a handful of writers talking more generally about their writing, about the themes and topics which their broader genre is currently addressing, about on-going developments in their particular literary area, comparing and contrasting their own work and process with each other and with the writers who’ve gone before them. It does happen, particularly with crime writers, but it’s still nowhere as prevalent as it is at SF conventions. I think that’s a shame, because audiences so clearly appreciate such wide-ranging discussion. It’s rarer still to see a fan/reviewer taking part in literary festival panels to broaden the debate with their perspective whereas such participation is an integral and valuable facet of convention programming.

Traditionally, at SF conventions, no one gets paid for the considerable amount of time they contribute, by which I mean none of the organising committee or any of those people who help out with such things as Ops, Publications, Tech and any amount of other vital support. Membership revenues cover the costs of venues and the various commercial services essential for the event to take place. Those authors who have been specifically invited as Guests of Honour have their expenses covered as a thank you for what will be a hard working weekend but they’re not paid a fee as such. Some conventions offer free memberships to other published authors on the programme and believe me, that’s always very much appreciated, but even then, those writers are expected to cover their own travel, hotel and sustenance expenses.

Is that fair? Well, an author assuredly has the opportunity to get far more from a convention than they do from a literary festival and not just a thoroughly enjoyable social event. It’s a weekend of networking and catching up on industry news, of benefiting from other writers’ experiences and perspectives, of learning things that are often directly relevant to whatever they’re working on or which will spark their imagination for a new project, of engaging with established fans and readers new to their work, often getting valuable feedback and usefully thought-provoking questions. Opportunities for paying work often follow from contacts made and conversations had.

Which is great – as long as you can afford to get to the convention in the first place and with authors’ incomes dropping year on year, that’s becoming an increasing issue for many SF&F writers. Plus the line between fan-run, non-profit events and overtly commercial enterprises has become blurred in some cases in recent years. I’ve been invited to SF&F events where I’ve discovered media guests are being paid fat appearance fees but the writers are expected to participate for free, in some cases without even expenses paid. You won’t be surprised to learn I declined. Then there have also been events where I’ve discovered some writers’ expenses are covered at the organisers’ discretion – but not others. That’s wholly unacceptable as far as I am concerned.

So do I think writers appearing at literary festivals should get paid? Yes. They’re doing a job of work to a professional standard and everyone else involved is getting paid.

Do I think programme participants at SF conventions should be paid? In an ideal world, yes – but doing that would force up the cost of convention memberships far beyond what the other fans could afford, especially once their hotel and other expenses are factored in.

Should all conventions factor in the cost of free memberships for programme participants? Personally, I’d very much like to see it. It’s saying ‘this is the value we put on your contribution and thank you’ as opposed to ‘kindly pay us for the privilege of working this weekend’ but once again, that would force up the cost of membership for everyone else with implications for levels of attendance and thus funds for essential expenses. Some conventions will decide their event can sustain this, others will decide that they can’t. As I know from my participation in running Eastercon 2013, a big convention’s budget is a dauntingly complex affair.

But the crucial distinction remains. Literary festivals and other commercial enterprises should pay the writers without whom there’d be no event. Non-profit conventions where readers and writers are sharing their common passion as fans are something else entirely.